2022第44卷第10期

“上携程APP,刷华夏信用卡,享受随机最高减666元!”这是携程与华夏信用卡于2020年联合推出的一项随机立减活动,消费者在携程旅行手机客户端订购产品并使用华夏信用卡支付时,有机会获得最低20元、最高666元的随机立减优惠。随着移动支付手段的蓬勃发展,越来越多的公司开始使用这样的随机立减活动来吸引消费者。随机立减是现金折扣的一种特殊形式,消费者会基于事先设定的概率因素获得不同金额的折扣(Alavi等,2015)。常见的随机立减模式包括“最高立减”“最低立减”和“范围立减”等。作为现金折扣的特殊形式,随机立减也具备现金折扣的优点:对营销者而言,现金折扣有助于使产品或服务在越发苛求的消费者心中抢占突出位置(Laran和Tsiros,2013;Alavi等,2015;Tan等,2019);对消费者而言,支付的“痛苦”会因为现金折扣的存在而有所减轻,并能为自己提供惊喜感(Choi等,2011;Laran和Tsiros,2013;Tan等,2019)。

随机立减也有其特殊性。在传统的现金折扣模式中,所有人均得到同等折扣,因此不同消费者之间对价格的公平性感知是相似的。但是,随机立减由于具有随机性,对于消费者而言,随机就意味着自己可能收获与他人不同的折扣。不同的随机立减策略意味着消费者可能将店家声称的折扣上限、折扣下限、或其他消费者获得的折扣金额作为参照系,以衡量自己所获得的折扣与参照系之间的差异。这种差异会影响消费者对价格公平性的感知。价格公平感与购买意愿具有正向相关关系(Kahneman 等,1986;Etzioni,1988)。价格公平感知较高时,消费者对产品的评价较高,购买意愿较高;而价格公平感知较低则可能引起消费者的一系列负面反馈(Huppertz等,1978;Campbell,1999;Chen等,2010)。

因此,营销者需要了解几种随机立减策略是否会造成不同的产品营销效果。何种随机立减模式最有利于提升购买意愿?引起不同随机立减模式和购买意愿间关系的背后机制是否是价格公平感知?营销者可以采取哪些干预手段来降低某种随机立减策略可能引起的价格不公平感知,从而提升购买意愿?本研究旨在有效回答这些问题,以更好地指导营销者推动更加有效的随机立减价格策略。

通过三个实验,本研究发现,不同的随机立减策略对消费者购买意愿具有不同程度的影响。消费者优先以折扣上限作为参考系,仅呈现折扣上限的随机立减模式比仅呈现折扣下限的随机立减模式引起更高的价格不公平感知,进而降低购买意愿。这些发现具有重要的理论贡献。首先,过去的研究对价格促销对购买意愿的积极影响进行了许多讨论(Chen等,2010;Tan和Chen,2021)。但是,随机立减作为一种特殊的不确定性折扣形式,与传统的价格促销模式具有较大区别,相关的研究成果不多。虽然以往那些针对不确定性现金折扣的研究结论一定程度上可以为随机立减模式的促销效果讨论提供一些指引(Laran 和Tsiros,2013;De Vries 和Zhang,2020;Gupta等,2020),但是却并不能有助于比较分析不同随机立减策略的效果。本文的研究对于这一领域的研究具有较大的补充,有助于后续研究讨论针对不同随机立减模式设计不同的辅助策略。其次,本文发现了消费者优先以折扣上限为锚定基准点,而在引入其他消费者所获折扣作为参考系后,消费者会优先评估自己与其他消费者所支付价格之间的公平性。这对于锚定效应和心理参考系问题的相关研究成果进行了重要的补充。

二、理论分析与研究假设(一)随机立减策略、价格公平感知与购买意愿

价格促销是吸引消费者的重要手段,能够通过吸引新的消费者和刺激忠诚消费者提高购买量来提升销售额(Chen等,2010)。消费者从一次购买中得到的效用是获得效用和交易效用的总和,获得效用是指消费者从所购产品中获得的实际效用,交易效用是指消费者从交易中收获的感知价值(Thaler,1983,1985;Cai等,2016)。价格促销正是通过传达一种“实惠交易”的感知来为消费者提供交易效用,从而促进购买意愿提升(Lichtenstein等,1990;Chandon等,2000;Heilman等,2002)。

现金折扣是价格促销的常见形式,包括确定性的现金折扣和不确定性的现金折扣。随机立减属于不确定性的现金折扣,主要表现为商家为消费者提供一个现金折扣的机会,但并不明确指出折扣金额。作为一种现金折扣,随机立减能够降低消费者实际支付的价格,有助于提升期望的交易效用(Choi等,2011),也因此有助于提升消费者的购买意愿。然而,随机立减因其不确定性特征,又与传统的现金折扣有所区别。一方面,不确定性为消费者带来更强的体验感,有助于提升对产品的积极感知(Laran和Tsiros,2013;Gupta等,2020)。另一方面,不确定性也使得消费者的心理参考价格发生不同程度的改变,因而不同的随机立减模式并不一定总是像传统的现金折扣那样提升消费者的交易效用。

常见的随机立减模式包括:(1)提供折扣金额下限,如“最低可省5元”;(2)提供折扣金额上限,如“最高可省50元”;(3)提供折扣金额上限和下限,如“随机立减5至50元”。由于不同模式规划了价格折扣范围的不同表达形式,消费者对自己应得折扣的心理预期会依据锚定的参考系不同而不同,并因此引起程度不同的价格公平感知(Choi等,2011)。消费者的购买意愿通常依赖于消费者对价格公平性的感知,当价格公平感知上升时,消费者的积极反馈提升;当价格公平感知下降时,则会出现一系列的负面反馈(Kahneman等,1986;Etzioni,1988)。比如,消费者的支付意愿正向依赖于价格公平感知(Kahneman等,1986);价格公平感知下降会引起消费者的负面情绪,进而引起企业的销售额和整体利润下降(Franciosi等,1995)。在对产品的评价上,价格公平感知也会正向影响消费者对产品的评价和购买意愿(Jones等,2019;Mori,2021)。

价格公平感知是指消费者对商家所提供价格的一种感知公平性判断,是消费者将支付价格与心理参考价格相比较的结果(Haws和Bearden,2006;Jin等,2014)。当感知支付价格比心理参考价格更高时,消费者的价格公平感知会降低。心理参考价格是消费者基于某些特定参考系而形成的对产品价格的预期(Bolton等,2003;Haws 和Bearden,2006;Chen等,2010)。由于消费者心理参考价格并非是客观实际的价格,因此价格公平感知是一种主观判断(Chen等,2010)。在实际支付价格不变的情况下,心理参考价格的不同会导致不同程度的价格公平感知。基于锚定效应理论,消费者对价格的数值判断会与已经设定的标准同化,即消费者的心理参考价格会趋向于某个既有参考系(Sailors 和 Heyman,2011)。评估情境的不确定性越强,消费者对既有参考系的依赖程度越强(Wu等,2008)。也就是说,在随机立减的情境中,由于价格信息具有高度不确定性,因此消费者对价格公平性的感知会高度依赖于给定的锚定参考值(Wong 和Kwong,2000)。

基于锚定效应理论,消费者会依据参考系的绝对值来评估自己获得的收益(Choi和Mattila,2018)。在随机折扣的情境中,消费者对于价格的感知是具有高度不确定性的,为了尽量降低不确定性,消费者会更依赖于该情境中任何可能的确定性因素(Moon和 Nelson,2020)。在仅呈现折扣下限的随机立减模式中,消费者唯一接收到的确定性因素就是随机立减的下限,即“至少能获得的折扣金额”,这一金额也因而成为唯一的价格参考信息。由于给定唯一锚定点时消费者的价值预期总是会尽量接近于该锚定点(Simonson 和 Drolet,2004;Wong 和 Kwong,2000),此时,消费者的心理参考价格是依据原价减去折扣下限来决定的,在实际的折扣抽取完成后,消费者会发现自己实际支付的价格低于其心理参考价格,因此价格公平感知较高。反之,在仅呈现折扣上限的随机立减模式中,消费者唯一接收到的价格参考信息是随机立减的上限,即“最多能获得的折扣金额”,此时,消费者的心理参考价格是依据原价减去折扣上限来决定的,因此消费者会发现自己实际支付的价格高于预先设定的心理参考价格,故而价格公平感知较低。由于更低的价格公平感知会导致更低的购买意愿(Campbell,1999),所以仅呈现折扣上限(最高可减)模式会比仅呈现折扣下限(最低可减)模式引起消费者更低的购买意愿。

呈现折扣范围(即同时呈现折扣上下限)的随机立减模式同时给定了两个锚定参考点,如果消费者优先以下限为锚定点,则消费者的价格公平感知和购买意愿应当与仅呈现折扣下限模式相似;反之,如果消费者优先以上限为锚定点,则价格公平感知和购买意愿应当与仅呈现折扣上限模式相似。研究指出,在给定两个锚定参考值的情况下,人们会优先依赖于头部指标,即消费者的关注点会更侧重于所设定的上限,更容易表现出接近于所设定上限的锚定效应(Sailors 和 Heyman,2011)。也就是说,在同时具有上下限的情况下,消费者会优先以折扣上限为锚定基准点来形成心理参考价格。

综上所述,只要消费者接收到折扣上限信息,总是会优先以折扣上限为锚定基准点,从而形成心理参考价格。在仅呈现折扣上限和呈现折扣上下限范围两种随机立减模式中,由于消费者实际获得的折扣低于锚定基准点(折扣上限),因此消费者会将其视为自己能够得到却没能得到的优惠,这种错失的优惠会被视作是一种损失(Chen等,2010)。因此,接收到折扣上限信息的模式总是比仅接收折扣下限信息的模式引起消费者更低的价格公平性感知,购买意愿也随之降低。

基于以上讨论,我们提出以下假设:

假设1:呈现折扣上限比仅呈现折扣下限引起更低的购买意愿;

假设2:价格公平感知在随机立减策略与购买意愿之间的关系中起中介作用。呈现折扣上限负向影响价格公平感知,而价格公平感知正向影响购买意愿。

(二)额外参考系的调节作用

过去的研究指出,其他消费者的支付价格是消费者在形成心理参考价格时所依赖的重要参考系之一(Haws 和 Bearden,2006;Chen等,2010)。消费者在购后意识到自己错失了一项促销活动时会产生强烈的负面反馈,因为他们认为自己比其他消费者支付了更高的价格。也就是说,尽管锚定参考系的不同引起消费者不同的心理参考价格,引起不同程度的价格公平感知,消费者更为在意的是自己是否比其他消费者支付了更高的价格。

换句话说,如果将其他消费者获得的同等金额折扣作为额外参考系引入随机立减策略之中,消费者虽然仍然会优先以折扣上限为锚定基准点形成心理参考价格,但只要消费者意识到自己并没有比其他消费者支付了更高的价格,呈现折扣上限所造成的购买意愿下降的效应将会有所减弱。消费者虽然因为自己获得的折扣低于随机立减上限而引起价格公平感知降低,但由于被告知其他消费者也获得了同等金额的折扣,那么消费者的负面反馈会有所减轻,随机立减策略对购买意愿的主效应也会减弱。

根据以上讨论,我们提出以下假设:

假设3:额外参考系调节随机立减策略对购买意愿的影响。引入同等金额折扣的额外参考系后,呈现折扣上限的随机立减策略对购买意愿的负向影响减弱。

三、前 测我们选取了两款较为中性的产品(中性卫衣和智能保温杯)作为实验刺激物,以降低性别或产品款式对实验结果可能造成的干扰。同时,为了尽量降低整数效应或尾数效应对实验结果的影响,我们将实验刺激物的原价设定为195元。选定产品后,我们首先希望确定实验刺激物的合理折扣范围。既有研究在设定概率折扣问题时,在折扣下限为0的情况下,通常将概率折扣上限设定为50%,而概率折扣期望为25%(Alavi等,2015;Tan 和 Chen,2021)。另有研究指出,缩小随机折扣的折扣范围会降低随机折扣的不确定性,因而在讨论这些折扣对消费者行为的后续影响中,起到决定性作用的可能不再是折扣和参考价格本身,而是消费者的风险规避需求(De Vries 和 Zhang,2020)。因此,在讨论随机折扣问题时,应当围绕25%的期望值,设定较大的上下限范围以确保折扣体现出足够的不确定性。

除了以既有研究作为实验操控设定的参考以外,我们也通过一个前测实验来确定实验设定的合理性。被试者来自网络被试招募平台(问卷星),共101人,其中64.4%为女性,平均年龄30.0岁。所有被试均会看到一则标价为195元的智能保温杯的图片和文字介绍,并需要回答按照自己以往的购物经验,如果商家想要为这款保温杯推出随机立减的折扣活动的话,商家通常而言设置的折扣下限金额和折扣上限金额是多少。被试也将看到一则标价195元的中性卫衣的图片和文字介绍,并回答如果为这款卫衣推出随机立减的折扣活动的话,商家通常设置的折扣上下限金额是多少。结果表明,对于保温杯而言,消费者经验表明的折扣下限均值及方差为M=8.02、SD=6.54;折扣上限的均值及方差为M=92.96、SD=39.30。对于卫衣而言,折扣下限的均值及方差为M=7.59、SD=5.79,折扣上限的均值及方差为M=92.65、SD=39.53。因此,两个产品实际的折扣上下限设定应当落于各自的均值加减一个方差的范围之内。

因此,我们最终将实验刺激物的折扣上限确定为95元(略低于50%的折扣率),下限确定为5元(略高于0的折扣率)。这种设定既遵循了既有研究的思路,又符合实际的前测结果,同时也保证了围绕25%折扣率的期望设定较大的上下限范围以体现出足够的不确定性。

四、实验设计与假设检验(一)实验一

被试者来自网络被试招募平台(问卷星),共206人,其中46.6%为女性,平均年龄31.1岁。实验一采用单因素组间设计,通过对只呈现折扣下限、只呈现折扣上限以及呈现折扣上下限范围、不呈现折扣范围这四种随机立减模式对消费者价格公平感知和购买意愿的影响进行两两比较,验证假设1和假设2。

1.实验流程

被试被邀请参与一家网店的新品促销活动,被随机分配到四种不同模式的随机立减策略刺激中。首先,所有被试均会看到一则中性卫衣的图片广告,并告知该卫衣标价为195元。随后,只呈现折扣下限模式中,被试被告知该店为这款卫衣推出了新款促销活动,有机会获得最低5元的现金折扣;只呈现折扣上限模式中,被试被告知有机会获得最高95元的现金折扣;呈现折扣上下限范围模式中,被试被告知有机会获得最低5元、最高95元的现金折扣;不呈现折扣范围模式中,被试只是被告知有机会获得现金折扣。随后,被试被邀请通过一个网络页面在线抽取随机立减金额,所有被试都将抽到50元的现金折扣,并被告知最后需要为购买卫衣支付的价格为145元。

完成折扣抽取后,被试需要回答两个价格公平感知测项(Jin等,2014):“你在多大程度上认为自己所需支付的价格是公平的”“你在多大程度上认为自己抽到的折扣是公平的”(1=非常不公平,9=非常公平;r=0.71,p<0.001),和一个购买意愿测项:“你在多大程度上愿意购买这款卫衣”(1=非常不愿意,9=非常愿意)。随后,被试填写实验所需的人口统计信息。

2.实验结果

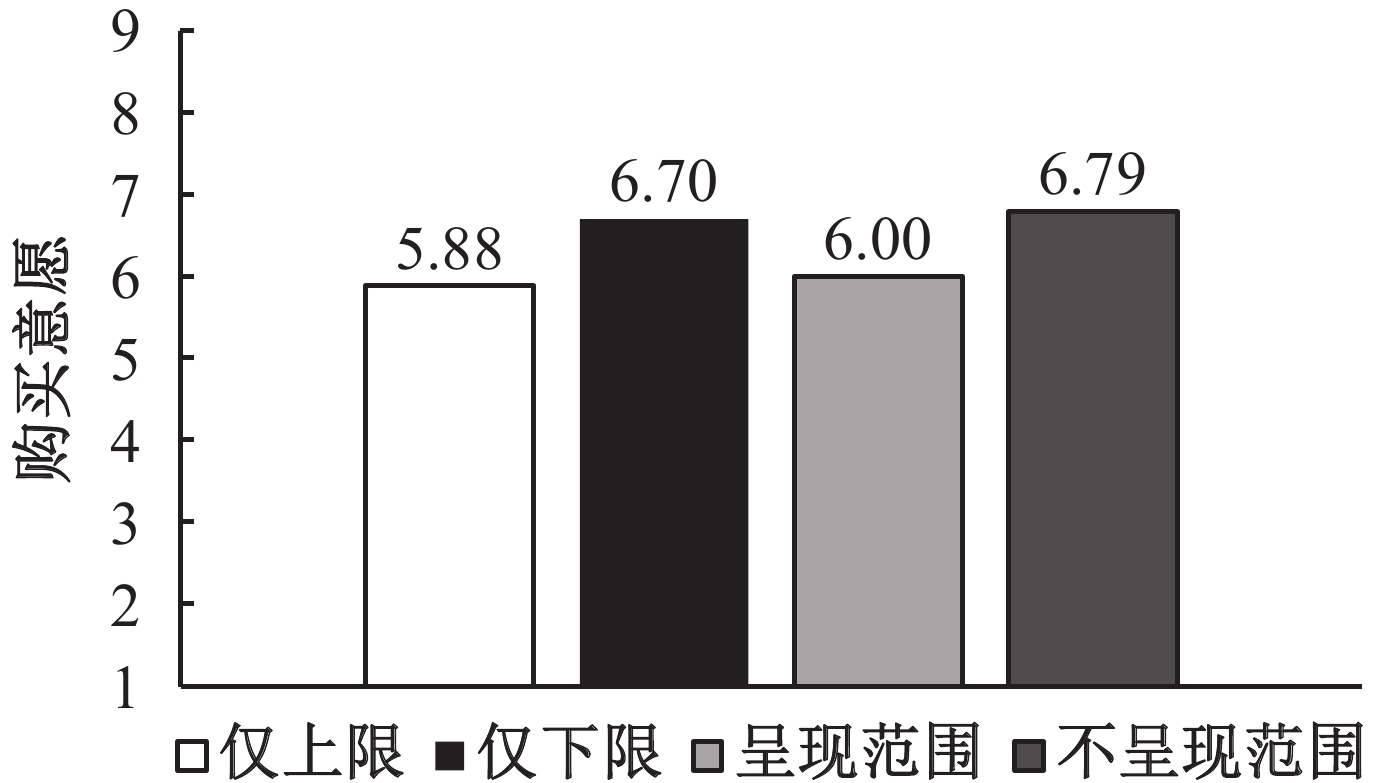

单因素方差分析结果表明,四组被试的购买意愿存在显著差异(F=2.58,p=0.055,η2=0.037)。仅呈现折扣上限组的购买意愿显著低于下限组(M上限=5.88 vs. M下限 =6.70;t=−2.03,p=0.044)和不呈现折扣范围组(M上限=5.88 vs. M无范围=6.79;t=−2.16,p=0.032);仅呈现折扣下限组和不呈现折扣范围组的购买意愿没有显著区别(t=−0.20,p>0.84)。值得注意的是,呈现折扣范围组的购买意愿与仅呈现折扣上限组没有显著区别(M范围=6.00 vs. M上限=5.88;t=−0.28,p>0.77),但显著低于仅呈现折扣下限组(M范围=6.00 vs. M下限=6.70;t=−1.75,p=0.081)和不呈现折扣范围组(M范围=6.00 vs. M无范围=6.79;t=−1.89,p=0.060),结果见图1。

|

| 图 1 各组被试的购买意愿 |

也就是说,当消费者接收到折扣上限的信息时(仅呈现折扣上限、呈现折扣上下限范围),无论是否接收到折扣下限,消费者都优先以折扣上限作为参考系,与自己所得的随机立减折扣进行对比,因为感知自己获得的折扣较参考系低,因而产生价格不公平感知,并因此降低了对目标产品的购买意愿。为此,我们检验了价格公平感知在此过程中所起的中介作用。

我们采用SPSS的PROCESS方法(Hayes,2017)进行中介效应检验,以四组随机立减模式为自变量生成三个虚拟变量(d1: 0=仅呈现折扣上限,1=仅呈现折扣下限,0=呈现折扣上下限范围,0=不呈现折扣范围;d2: 0=仅呈现折扣上限,0=仅呈现折扣下限,1=呈现折扣上下限范围,0=不呈现折扣范围;d3: 0=仅呈现折扣上限,0=仅呈现折扣下限,0=呈现折扣上下限范围,1=不呈现折扣范围),以两个价格公平感知测项的均值生成价格公平感知指数作为中介变量,购买意愿为因变量,采用模型4,重复样本数目5000,置信区间水平为95%。

结果表明,d1和d3对价格公平感知的主效应显著。仅呈现折扣下限比仅呈现折扣上限的随机立减模式的价格公平感知更高(β=0.92,se=0.33,t=2.80,p=0.006),不呈现折扣范围也比仅呈现折扣上限的随机立减模式的价格公平感知更高(β=0.73,se=0.34,t=2.14,p=0.033)。d2的主效应不显著,即呈现上下限范围的模式与仅呈现折扣上限的模式对消费者的价格公平感知的影响没有区别(p>0.35),结果见表1。

| 前置变量 | 结果变量 | |||||||

| 价格公平感知(中介) | 购买意愿(因变量) | |||||||

| β | se | t | β | se | t | |||

| 仅呈现下限(d1) | a1 | 0.92 | 0.33 | 2.80** | c1 | −0.04 | 0.27 | −0.16 |

| 呈现上下限范围(d2) | a2 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.93 | c2 | −0.17 | 0.26 | −0.66 |

| 不呈现上下限范围(d3) | a3 | 0.73 | 0.34 | 2.14** | c3 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.80 |

| 价格公平感知 | b | 0.94 | 0.06 | 16.70*** | ||||

| R2 = 0.04

F(3, 202) = 3.14, p = 0.026 |

R2 = 0.60

F(4, 201) = 74.36, p < 0.001 |

|||||||

| 注:仅呈现折扣上限组为基准对照组;c1、c2、c3表示加入中介变量后,自变量各维度的直接效应;a显著而c不显著,说明价格公平感知在d1、d3情境中完全中介;*表示p<0.10,**表示p<0.05,***表示p<0.001。 | ||||||||

对价格公平感知在随机立减模式对购买意愿影响的间接效应结果表明,d1通过价格公平感知影响购买意愿的间接效应显著:仅呈现折扣上限比仅呈现折扣下限的随机立减模式引起了更高的价格不公平感知,因而引起了更低的购买意愿,价格公平感知在这一过程中起中介作用,CI值显著不包括0。d3通过价格公平感知影响购买意愿的间接效应也显著:仅呈现折扣上限比不呈现折扣范围的随机立减模式引起了更高的价格不公平感知,进而引起更低的购买意愿,价格公平感知起中介作用,CI值显著不包括0(见表2)。

| 随机立减策略 | 效应值 | BootSE | Bootstrap 95% CI | ||

| 下限 | 上限 | ||||

| 价格公平感知

的中介效应 |

仅呈现下限 | 0.86 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 1.49 |

| 呈现上下限范围 | 0.29 | 0.32 | −0.33 | 0.92 | |

| 不呈现上下限范围 | 0.68 | 0.32 | 0.07 | 1.33 | |

| 注:仅呈现折扣上限组为基准对照组。 | |||||

实验一的结果证明了假设1和假设2,即呈现折扣上限比呈现折扣下限引起更高的价格不公平感知,进而降低购买意愿。通过与两个控制组相对比(同时呈现上下限范围和不呈现折扣范围)确定了消费者优先以折扣上限为参考系,与自身获得的实际折扣相对比,因而降低了对价格的公平感知,从而降低购买意愿。当不呈现折扣上限时,消费者不会由于与参考系对比而产生低价格公平感,因而不会降低购买意愿。

(二)实验二

被试者来自网络被试招募平台(问卷星),共176人,其中57.4%为女性,平均年龄30.3岁。实验二旨在变更操控方式从而再次验证假设,以证明本研究效应的稳健性。与实验一不同,实验二改变了两个实验组和两个控制组对于折扣金额的设定,以证明在没有明确给定折扣范围时,获得不同折扣的消费者对价格公平性的感知没有区别,对目标产品的购买意愿也没有区别;而给定折扣上限或下限时,消费者优先以折扣上限作为参考,即使在呈现折扣上限的情境中获得的实际折扣高于呈现折扣下限的情境,消费者对价格公平性的感知和对目标产品的购买意愿也会降低。

1.实验流程

被试被邀请参与一家网店的新品促销活动,被随机分配到四种不同模式的随机立减策略刺激中(只呈现折扣下限、只呈现折扣上限以及两个不呈现折扣范围的控制组)。首先,所有被试均会看到一则智能保温杯的图片广告,并告知该保温杯标价为195元。随后,在只呈现折扣下限模式中,被试被告知该店为这款保温杯推出了新款促销活动,有机会获得最低5元的现金折扣;只呈现折扣上限模式中,被试被告知有机会获得最高95元的现金折扣;两个不呈现折扣范围的组别中,被试只是被告知有机会获得现金折扣。随后,被试被邀请在一个网络页面中在线抽取随机立减金额,只呈现折扣下限组的被试抽到的是45元的现金折扣,只呈现折扣上限组的被试抽到的是55元的现金折扣,两个控制组的被试随机抽取到45元或55元的现金折扣。也就是说,只呈现折扣下限组和其中一个控制组的被试会被告知自己购买保温杯所需支付的价格是150元;只呈现折扣上限组和另一个控制组的被试会被告知购买保温杯所需支付的价格是140元。

完成折扣抽取后,与实验一相同,被试仍需要回答两个价格公平感知测项(r=0.67,p<0.001)和一个购买意愿测项,并填写人口统计信息。

2.实验结果

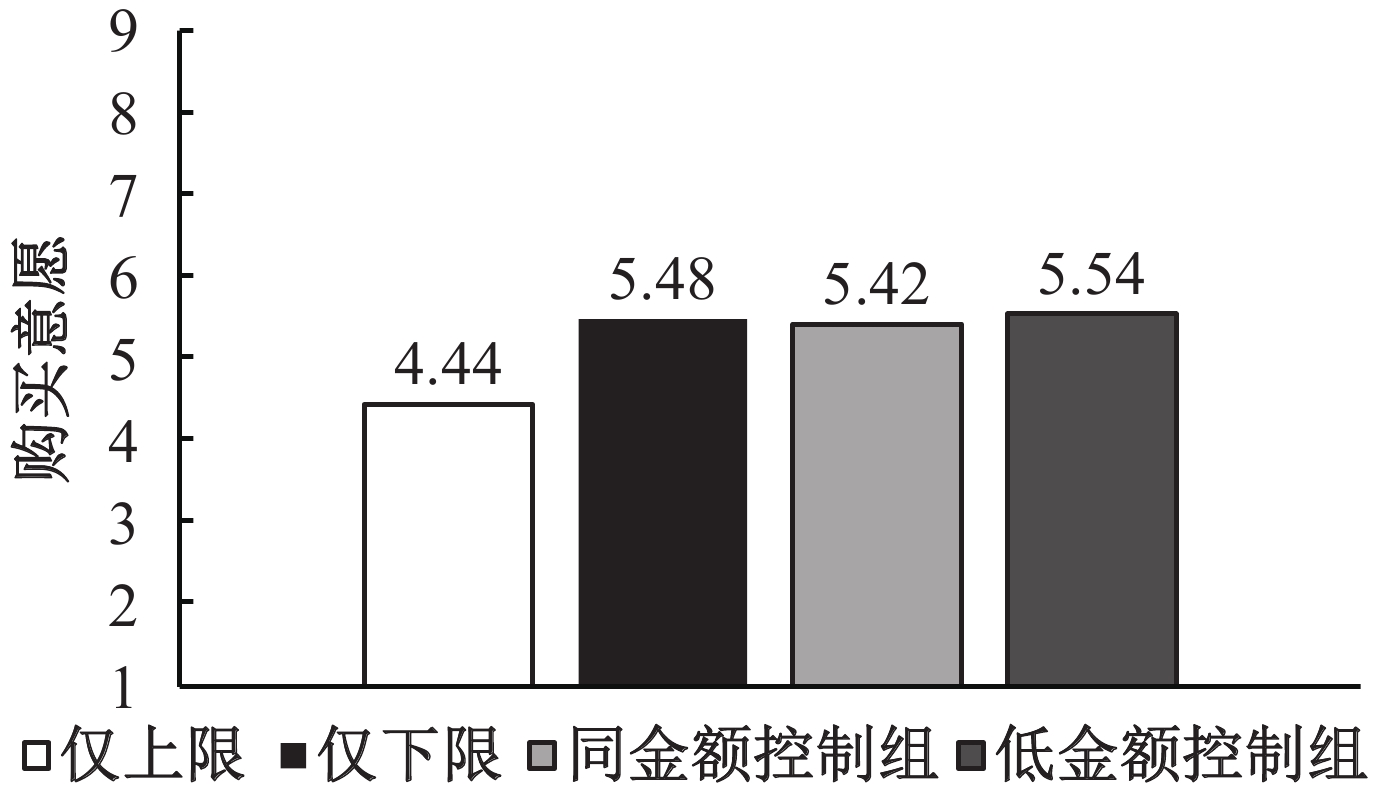

单因素方差分析结果表明,四组被试的购买意愿存在显著差异(F=2.58,p=0.055,η2=0.043)。其中,仅呈现折扣上限组的购买意愿显著低于下限组(M上限=4.44 vs. M下限=5.48;t=−2.28,p=0.024)和获得同金额折扣(55元)的控制组(M上限=4.44 vs. M同金额控制组= 5.42;t=−2.08,p=0.039)以及获得更低金额折扣(45元)的控制组(M上限=4.44 vs. M低金额控制组=5.54;t=−2.43,p=0.016);仅呈现折扣下限组和获得同金额折扣(45元)的控制组的购买意愿没有显著区别(M下限=5.48 vs. M同金额控制组=5.54;t =−0.15,p>0.88)、和获得更高折扣金额(45元)的控制组的购买意愿也没有显著区别(M下限=5.48 vs. M低金额控制组=5.42;t=0.14,p> 0.89)。值得注意的是,两个不呈现折扣上下限的控制组虽然获得的实际折扣金额不同,但购买意愿并没有显著区别(t=−0.28,p>0.78),结果见图2。

|

| 图 2 各组被试的购买意愿 |

也就是说,当消费者接收到折扣上限的信息时(仅呈现折扣上限、呈现折扣上下限范围),无论是否接收到折扣下限,消费者都优先以折扣上限作为参考系,与自己所得的随机立减折扣进行对比,因为感知自己获得的折扣较参考系低,因而产生价格不公平感知,并因此降低了对目标产品的购买意愿。当没有接收到折扣范围作为参考系时,无论消费者实际获得了多少折扣,对目标产品的购买意愿都没有区别。为此,我们检验了价格公平感知在此过程中所起的中介作用。

我们采用SPSS的PROCESS方法(Hayes,2017)进行中介效应检验,以四组随机立减模式为自变量生成三个虚拟变量(d1: 0=仅呈现折扣上限,1=仅呈现折扣下限,0=获得55元折扣的控制组,0=获得45元折扣的控制组;d2: 0=仅呈现折扣上限,0=仅呈现折扣下限,1=获得55元折扣的控制组,0=获得45元折扣的控制组;d3: 0=仅呈现折扣上限,0=仅呈现折扣下限,0=获得55元折扣的控制组,1=获得45元折扣的控制组),以两个价格公平感知测项的均值生成价格公平感知指数作为中介变量,购买意愿为因变量,采用模型4,重复样本数目5000,置信区间水平为95%。

结果表明,d1对价格公平感知的主效应显著。仅呈现折扣下限比仅呈现折扣上限的随机立减模式的价格公平感知更高(β=1.04,se=0.35, t=2.96,p=0.004),结果见表3。

| 前置变量 | 结果变量 | |||||||

| 价格公平感知(中介) | 购买意愿(因变量) | |||||||

| β | se | t | β | se | t | |||

| 仅呈现下限(d1) | a1 | 1.04 | 0.35 | 2.96** | c1 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.39 |

| 同金额控制组(d2) | a2 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 1.59 | c2 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 1.35 |

| 低金额控制组(d3) | a3 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 1.72* | c3 | 0.58 | 0.34 | 1.70 |

| 价格公平感知 | b | 0.87 | 0.07 | 11.83*** | ||||

| R2 = 0.05,

F(3, 172) = 2.95, p = 0.035 |

R2 = 0.47,

F(4, 171) = 38.48, p < 0.001 |

|||||||

| 注:仅呈现折扣上限组为基准对照组;c1、c2、c3表示加入中介变量后,自变量各维度的直接效应;a显著而c不显著,说明价格公平感知在d1情境中完全中介;*表示p<0.10,**表示p<0.05,***表示p<0.001。 | ||||||||

对价格公平感知在随机立减模式对购买意愿影响的间接效应结果表明,d1通过价格公平感知影响购买意愿的间接效应显著:仅呈现折扣上限比仅呈现折扣下限的随机立减模式引起了更高的价格不公平感知,因而引起了更低的购买意愿,价格公平感知在这一过程中起中介作用,CI值显著不包括0,结果见表4。

| 随机立减策略 | 效应值 | BootSE | Bootstrap 95% CI | ||

| 下限 | 上限 | ||||

| 价格公平感知

的中介效应 |

仅呈现下限 | 0.90 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 1.48 |

| 同金额控制组 | 0.50 | 0.34 | −0.17 | 1.15 | |

| 低金额控制组 | 0.52 | 0.29 | −0.04 | 1.11 | |

| 注:仅呈现折扣上限组为基准对照组。 | |||||

实验二的结果再次证明了假设1和假设2,即呈现折扣上限比呈现折扣下限引起更高的价格不公平感知,进而降低购买意愿。不仅如此,即使呈现折扣上限模式比呈现折扣下限模式使消费者获得的实际折扣金额更高,消费者仍然会持有更高的价格不公平感知和购买意愿。在不呈现任何折扣金额参考的时候,不论实际折扣高还是低,消费者的价格公平感知和购买意愿是没有差异的,因此通过与控制组的比较,也进一步证明了消费者优先以折扣上限为参考系,与自身获得的实际折扣相对比,降低了对价格的公平感知,从而降低购买意愿。

(三)实验三

被试者来自网络被试招募平台(问卷星),共199人,其中59.8%为女性,平均年龄29.6岁。实验三旨在验证假设3,证明在引入额外参考系后,呈现折扣上限引起购买意愿降低的效应会减弱,消费者购买意愿会重新提升。

1.实验流程

实验采取2(随机立减模式:仅呈现下限vs.仅呈现上限)×2(额外参考系:有vs.无)双因素组间设计。首先,被试会被分配到随机立减模式的组间设计中,被试被告知有朋友参与了一项保温杯的新品促销随机立减活动(与实验二相同,标价为195元),一组被试看到的活动简介是有机会获得最低5元的现金折扣(仅呈现下限),另一组被试看到的活动简介是有机会获得最高95元的现金折扣(仅呈现上限)。随后,被试会被分配到额外参考系的组间设计中,一组被试被告知朋友在此活动中抽到了50元的现金折扣,并邀请被试参与在线抽奖;另一组被试仅被告知朋友参与了此项活动获得了现金折扣,并邀请被试参与在线抽奖。随后,被试被邀请抽取随机立减折扣,所有被试都会抽到50元的现金折扣。也就是说,所有被试会被告知购买保温杯所需支付的价格是145元。

完成折扣抽取后,被试仍需回答两个价格公平感知测项(r=0.68,p<0.001)和一个购买意愿测项,并填写实验所需的人口统计信息。

2.实验结果

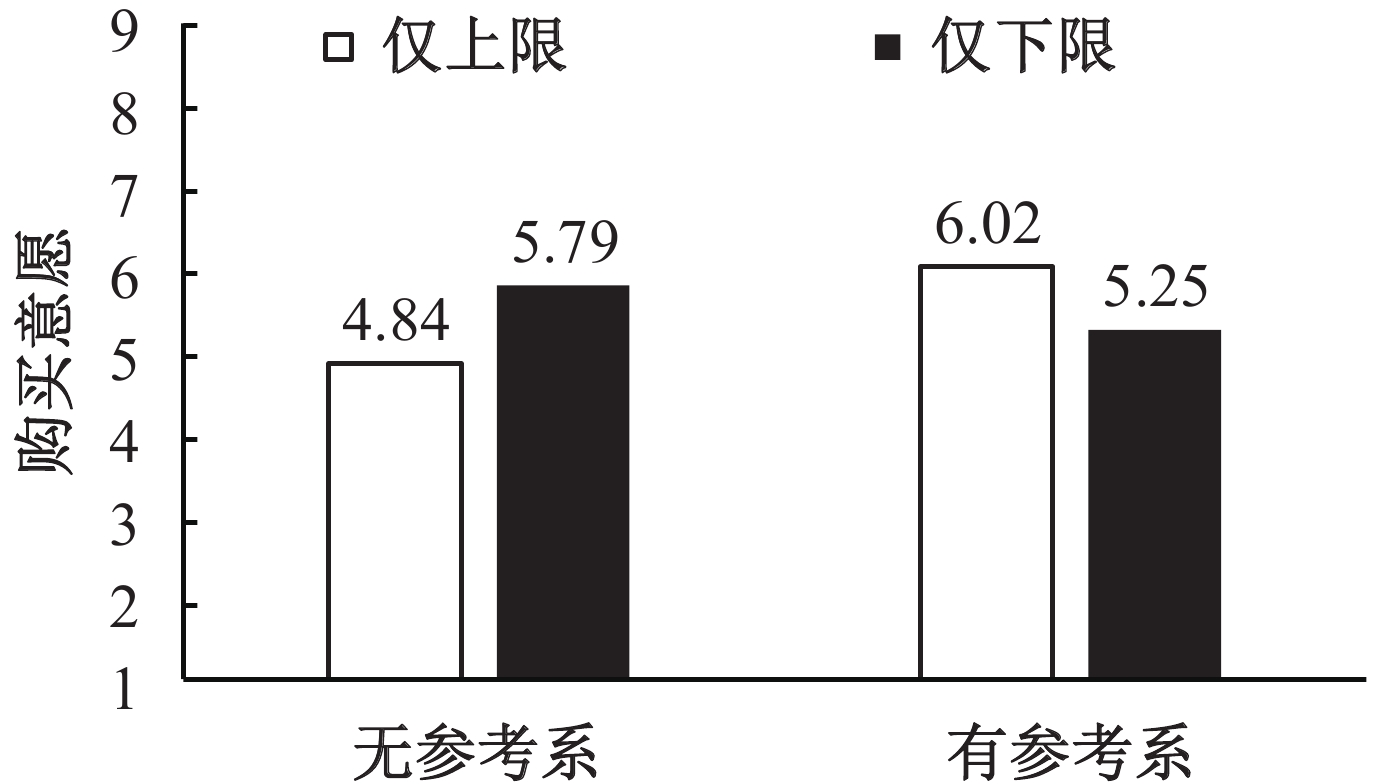

双因素方差分析结果表明,随机立减模式与额外参考系对购买意愿的交互效应显著(F=7.21,p=0.008,η2=0.036)。具体而言,在无额外参考系时,与前述实验结果相似,仅呈现折扣上限组的购买意愿显著低于仅呈现折扣下限组(M上限=4.84 vs. M下限=5.79;F=4.26,p=0.040,η2=0.021);在有额外参考系时,该效应发生反转,仅呈现折扣上限组的购买意愿边际显著地高于仅呈现折扣下限组(M上限=6.02 vs. M下限=5.25;F=2.98,p=0.086,η2=0.015),结果见图3。

|

| 图 3 各组被试的购买意愿 |

该结果再次证明,在没有额外参考系时,消费者优先以折扣上限作为参考系,与自己所得的随机立减折扣进行对比,因为感知自己获得的折扣较参考系低,因而降低价格公平感知,并因此降低了对目标产品的购买意愿。而在引入额外参考系后,消费者不再优先将自己所获与折扣上限进行比较,而是与额外的参考系进行比较,因此对目标产品的购买意愿重新提升。

我们采用SPSS的PROCESS方法(Hayes,2017)进行中介效应检验,以随机立减模式为自变量(0=仅呈现折扣上限,1=仅呈现折扣下限),以两个价格公平感知测项的均值生成价格公平感知指数作为中介变量,购买意愿为因变量,额外参考系为调节变量(0=有额外参考系,1=无额外参考系),采用模型7,重复测试样本数目5000,置信区间水平为95%。

结果表明,随机立减模式与额外参考系对价格公平感知的交互效应显著(R2-chng=0.05,F=9.41,p=0.003):在无额外参考系时,仅呈现折扣下限比仅呈现折扣上限的随机立减模式的价格公平感知更高(β=2.29,se=0.73,t=3.13,p=0.002);在有额外参考系时,仅呈现折扣下限仍然比仅呈现折扣上限的随机立减模式的价格公平感知更高(β=0.89,se=0.33,t=2.70,p=0.008),说明消费者总是优先依据折扣上限来形成对价格的公平性感知。另外,价格公平感知对购买意愿的主效应显著(β=1.05,se=0.07,t=15.98,p<0.001),结果见表5。

| 前置变量 | 结果变量 | |||||

| 价格公平感知(中介) | 购买意愿(因变量) | |||||

| β | se | t | β | se | t | |

| 随机立减模式 | −0.51 | 0.32 | −1.62 | −0.11 | 0.21 | −0.53 |

| 价格公平感知 | 1.05 | 0.07 | 15.98*** | |||

| 额外参考系 | −0.96 | 0.33 | −2.93** | |||

| 价格公平感知×额外参考系 | 1.40 | 0.46 | 3.07** | |||

| R2 = 0.05

F(3, 195) = 2.95, p = 0.014 |

R2 = 0.57

F(2, 196) = 127.66, p < 0.001 |

|||||

| 注:随机立减模式0=仅呈现折扣上限,1=仅呈现折扣下限;额外参考系0=有额外参考系,1=无额外参考系;*表示p<0.10,**表示p<0.05,***表示p<0.001。 | ||||||

进一步检验价格公平感知的中介作用发现,在无额外参考系的情境中,价格公平感知的中介效应显著,CI值显著地不包括0;而在有额外参考系的情境中,价格公平感知的中介效应不再显著,结果见表6。

| 随机立减策略 | 效应值 | BootSE | Bootstrap 95% CI | ||

| 下限 | 上限 | ||||

| 价格公平感知

的中介效应 |

无额外参考系 | 0.93 | 0.37 | 0.25 | 1.65 |

| 有额外参考系 | −0.54 | 0.32 | −1.18 | 0.08 | |

实验三的结果再次证明了假设1和假设2,即呈现折扣上限比呈现折扣下限引起更高的价格不公平感知,进而降低购买意愿。不仅如此,实验三的结果也证明了假设3,也就是说,消费者总是优先以折扣上限为参考来形成对价格折扣公平性的感知,在没有额外参考系的时候,这种价格折扣的不公平感知越强,对目标产品的购买意愿越低;然而,在引入额外参考系后,消费者会以其他消费者获得的折扣金额为参考,使得购买意愿重新提升。

五、结论与讨论(一)研究结论

通过三个实验,运用不同的实验刺激物、折扣范围设定以及有无参考系的设计,本研究发现,不同的随机立减策略对消费者购买意愿具有不同程度的影响。第一,消费者优先以折扣上限作为参考系,仅呈现折扣上限的随机立减模式比仅呈现折扣下限的随机立减模式引起更低的购买意愿。具体而言,消费者优先以折扣上限为参考系,与自身获得的实际折扣相对比,因而降低了对价格的公平感知,所以呈现折扣上限比呈现折扣下限的模式降低了消费者的购买意愿。第二,即使仅呈现折扣上限模式比仅呈现折扣下限模式使消费者获得的实际折扣金额更高,消费者仍然会持有更高的价格不公平感知和购买意愿。第三,随机立减策略对消费者购买意愿影响效应存在边界,在没有额外参考系的时候,消费者总是优先以折扣上限为参考来形成对价格折扣公平性的感知,这种价格折扣的不公平感知越强,对目标产品的购买意愿越低;在引入额外参考系后,消费者会以其他消费者获得的折扣金额为参考,当得知自己并未比其他消费者支付更高的价格,消费者的购买意愿会重新提升。

(二)管理启示

由于过去缺乏对不同随机立减策略促销效果的理论讨论,导致营销者在设计随机立减策略时,往往只关注于利用高额的折扣上限来吸引消费者的兴趣,如“有机会直接免单”“最高可享五折”等方式,给消费者以价格实惠的感觉。但是这往往只是营销噱头和手段,与线下购物通过实体抽奖券来获得不同金额的折扣的模式不同,互联网时代的随机立减策略通过机器算法设定能够轻松设置消费者可能获得的折扣概率,因此几乎没有消费者能够真正获得高额的折扣上限,根据本研究结论,这可能使得消费者在实际获得一个远低于折扣上限的折扣时会出现明显的负面反馈。本研究的发现有助于指导企业进行有效的随机立减策略设计,比如,已知消费者优先以折扣上限为参考标准,因此实际获得的折扣总是会低于或等于这一标准,导致价格公平感知下降,企业便需要酌情设置折扣上限,以尽量降低可能引起的消费者的负面反馈。本研究还发现引入额外参考系可以帮助削弱折扣上限模式可能引起的负面说服效果,因此营销人员可以通过其他诉求手段,向消费者传达其获得的折扣高于或等于其他消费者,以此重新获得较高的购买意愿。

(三)研究局限与展望

本研究在情境设置、样本和变量操控上具有一定的研究局限。首先,由于经费和形式的限制,本研究的随机立减活动全部是在虚拟的网络购物情境中完成的,被试通过网页想象自己在进行购物活动,只能看见一种设定好的产品图片及活动描述,并进行购买意愿打分测量。因此,被试不能进行实地感受和挑选产品,也不涉及实际的支付行为,这是本研究的一个局限。后续需要创造能够进行田野实验的条件,以验证在真实的消费环境中,本研究效应的真实表现形式。

其次,与第一个局限相对应的,本研究的被试并非实际某产品的消费者,而是参与虚拟购物环境的网络被试,因此,与实际具有某种购物需要并因此获得随机立减折扣的消费者相比,本研究的被试具有一定的局限。后续需要在真实消费场景进行探索,以验证当消费者自发具有某种消费需要(而非由实验操控启动的消费需要)时本研究效应的稳健性。

最后,为了简化理论探索的需要,本研究对自变量的不同组别设置得相当明确,即本研究将折扣范围上下限设置得非常明确且区别明显。然而,在实际的营销运用中,不同营销者对随机立减策略的设置可能具有各种十分细微的差别,比如,折扣范围上下限的区别大还是小?折扣范围上下限的设置是否具有尾数效应?是否通过其他手段暗示折扣范围?不同产品的价格敏感度是否会调节本研究效应?这些因素都是可能决定本研究效应影响范围的边界条件,需要在后续研究中进一步厘清。

| [1] | Ailawadi K L, Gedenk K, Langer T, et al. Consumer response to uncertain promotions: An empirical analysis of conditional rebates[J]. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 2014, 31(1): 94–106. |

| [2] | Alavi S, Bornemann T, Wieseke J. Gambled price discounts: A remedy to the negative side effects of regular price discounts[J]. Journal of Marketing, 2015, 79(2): 62–78. |

| [3] | Alderighi M, Nava C R, Calabrese M, et al. Consumer perception of price fairness and dynamic pricing: Evidence from Booking. com[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2022, 145: 769–783. |

| [4] | Attari A, Chatterjee P, Singh S N. Taking a chance for a discount: An investigation into consumers’ choice of probabilistic vs. sure price promotions[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2022, 143: 366–374. |

| [5] | Berns G S, McClure S M, Pagnoni G. Predictability modulates human brain response to reward[J]. Journal of Neuroscience, 2001, 21(8): 2793–2798. |

| [6] | Bolton L E, Keh H T, Alba J W. How do price fairness perceptions differ across culture?[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 2010, 47(3): 564–577. |

| [7] | Bolton L E, Warlop L, Alba J W. Consumer perceptions of price (un)fairness[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 2003, 29(4): 474–491. |

| [8] | Browne B A, Kaldenberg D, Brown D J. Games people play: A comparative study of promotional game participants and gamblers[J]. Journal of Applied Business Research, 2011, 9(1): 93–99. |

| [9] | Büyükdağ N, Soysal A N, Ki̇tapci O. The effect of specific discount pattern in terms of price promotions on perceived price attractiveness and purchase intention: An experimental research[J]. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 2020, 55: 102112. |

| [10] | Cai F Y, Bagchi R, Gauri D K. Boomerang effects of low price discounts: How low price discounts affect purchase propensity[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 2016, 42(5): 804–816. |

| [11] | Campbell M C. Perceptions of price unfairness: Antecedents and consequences[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 1999, 36(2): 187–199. |

| [12] | Caputo V, Lusk J L, Nayga R M. Am I getting a good deal? Reference-dependent decision making when the reference price is uncertain[J]. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 2020, 102(1): 132–153. |

| [13] | Chandon P, Wansink B, Laurent G. A benefit congruency framework of sales promotion effectiveness[J]. Journal of Marketing, 2000, 64(4): 65–81. |

| [14] | Chen S F S, Monroe K B, Lou Y C. The effects of framing price promotion messages on consumers’ perceptions and purchase intentions[J]. Journal of Retailing, 1998, 74(3): 353–372. |

| [15] | Chen W W, Tsai D, Chuang H C. Effects of missing a price promotion after purchasing on perceived price unfairness, negative emotions, and behavioral responses[J]. Social Behavior and Personality:An International Journal, 2010, 38(4): 495–507. |

| [16] | Chen Z, Zhu D H. Effect of dynamic promotion display on purchase intention: The moderating role of involvement[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2022, 148: 252–262. |

| [17] | Choi C, Mattila A S. The effects of internal and external reference prices on travelers’ price evaluations[J]. Journal of Travel Research, 2018, 57(8): 1068–1077. |

| [18] | Choi S, Stanyer M, Kim M. Consumer responses to the depth and minimum claimed savings of “Scratch and Save (SAS)” promotions[J]. Psychology & Marketing, 2010, 27(8): 766–779. |

| [19] | Chung J Y, Petrick J F. Mearsuring price fairness: Development of a multidimensional scale[J]. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 2015, 32(7): 907–922. |

| [20] | Dai H, Ge L, Li C, et al. The interaction of discount promotion and display-related promotion on on-demand platforms[J]. Information Systems and E-Business Management, 2021, 20(2): 285–302. |

| [21] | De Vries E L E, Zhang S. The effectiveness of random discounts for migrating customers to the mobile channel[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2020, 110: 272–281. |

| [22] | DelVecchio D, Krishnan H S, Smith D C. Cents or percent? The effects of promotion framing on price expectations and choice[J]. Journal of Marketing, 2007, 71(3): 158–170. |

| [23] | Dhar S K, González-Vallejo C, Soman D. Brand promotions as a lottery[J]. Marketing Letters, 1995, 6(3): 221–233. |

| [24] | Dhar S K, González-Vallejo C, Soman D. Modeling the effects of advertised price claims: Tensile versus precise claims?[J]. Marketing Science, 1999, 18(2): 154–177. |

| [25] | Dickson P R, Kalapurakal R. The use and perceived fairness of price-setting rules in the bulk electricity market[J]. Journal of Economic Psychology, 1994, 15(3): 427–448. |

| [26] | Ding Y, Zhang Y. Hiding gifts behind the veil of vouchers: On the effect of gift vouchers versus direct gifts in conditional promotions[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 2020, 57(4): 739–755. |

| [27] | Dutta S, Guha A, Biswas A, et al. Can attempts to delight customers with surprise gains boomerang? A test using low-price guarantees[J]. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 2017, 47(3): 417–437. |

| [28] | Etzioni A. The moral dimension: Toward a new economics[M]. New York: Free Press, 1988. |

| [29] | Ferguson J L, Ellen P S, Bearden W O. Procedural and distributive fairness: Determinants of overall price fairness[J]. Journal of Business Ethics, 2014, 121(2): 217–231. |

| [30] | Franciosi R, Kujal P, Michelitsch R, et al. Fairness: Effect on temporary and equilibrium prices in posted-offer markets[J]. The Economic Journal, 1995, 105(431): 938–950. |

| [31] | Gamliel E, Herstein R. To save or to lose: Does framing price promotion affect consumers’ purchase intentions?[J]. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 2011, 28(2): 152–158. |

| [32] | Gneezy U, List J A, Wu G. The uncertainty effect: When a risky prospect is valued less than its worst possible outcome[J]. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2006, 121(4): 1283–1309. |

| [33] | Goldsmith K, Amir O. Can uncertainty improve promotions?[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 2010, 47: 1070–1077. |

| [34] | Gong H, Huang J, Goh K H. The illusion of double-discount: Using reference points in promotion framing[J]. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2019, 29(3): 483–491. |

| [35] | Gordon K. The impermanence of being: Toward a psychology of uncertainty[J]. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 2003, 43(2): 96–117. |

| [36] | Gorji M, Siami S. How sales promotion display affects customer shopping intentions in retails[J]. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 2020, 48(12): 1337–1356. |

| [37] | Guha A, Biswas A, Grewal D, et al. Reframing the discount as a comparison against the sale price: Does it make the discount more attractive?[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 2018, 55(3): 339–351. |

| [38] | Gupta A, Eilert M, Gentry J W. Can I surprise myself? A conceptual framework of surprise self-gifting among consumers[J]. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 2020, 54: 101712. |

| [39] | Hariyana N, Wardani N I K, Salsabila N A. Discounts and promotions on purchase decision[J]. International Journal of Environmental, Sustainability, and Social Science, 2022, 2(2): 63–70. |

| [40] | Haws K L, Bearden W O. Dynamic pricing and consumer fairness perceptions[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 2006, 33(3): 304–311. |

| [41] | Hayes A F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach[M]. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Publications, 2017. |

| [42] | Heilman C M, Nakamoto K, Rao A G. Pleasant surprises: Consumer response to unexpected in-store coupons[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 2002, 39(2): 242–252. |

| [43] | Huppertz J W, Arenson S J, Evans R H. An application of equity theory to buyer-seller exchange situations[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 1978, 15(2): 250–260. |

| [44] | Jin L Y, He Y Q, Zhang Y. How power states influence consumers’ perceptions of price unfairness[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 2014, 40(5): 818–833. |

| [45] | Jones A L, Griffis S E, Schwieterman M A, et al. Examining the impact of shipping charge fairness on consumer satisfaction and behavior[J]. Transportation Journal, 2019, 58(2): 101–125. |

| [46] | Jung S, Cho H J, Jin B E. Does effective cost transparency increase price fairness? An analysis of apparel brand strategies[J]. Journal of Brand Management, 2020, 27(5): 495–507. |

| [47] | Kahneman D, Knetsch J L, Thaler R. Fairness and the assumptions of economics[J]. Journal of Business, 1986, 59(4): S285–300. |

| [48] | Kahneman D, Knetsch J L, Thaler R. Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: Entitlements in the market[J]. The American Economic Review, 1986, 76(4): 728–741. |

| [49] | Kaltcheva V D, Winsor R D, Patino A, et al. Impact of promotions on shopper price comparisons[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2013, 66(7): 809–815. |

| [50] | Kamen J, Toman R. Psychophysics of prices[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 1970, 7(February): 27–35. |

| [51] | Kaufmann P J, Ortmeyer G, Smith N C. Fairness in consumer pricing[J]. Journal of Consumer Policy, 1991, 14: 117–140. |

| [52] | Kwak H, Puzakova M, Rocereto J F. Better not smile at the price: The differential role of brand anthropomorphization on perceived price fairness[J]. Journal of Marketing, 2015, 79(4): 56–76. |

| [53] | Laran J, Tsiros M. An investigation of the effectiveness of uncertainty in marketing promotions involving free gifts[J]. Journal of Marketing, 2013, 77(2): 112–123. |

| [54] | Lastner M M, Fennell P, Folse J A G, et al. I guess that is fair: How the efforts of other customers influence buyer price fairness perceptions[J]. Psychology & Marketing, 2019, 36(7): 700–716. |

| [55] | Lee S, Yi Y. “Seize the deal, or return it losing your free gift”: The effect of a gift-with-purchase promotion on product return intention[J]. Psychology & Marketing, 2017, 34(3): 249–263. |

| [56] | Lee Y H, Qiu C. When uncertainty brings pleasure: The role of prospect imageability and mental imagery[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 2009, 36(4): 624–633. |

| [57] | Lehtimäki A V, Monroe K B, Somervuori O. The influence of regular price level (low, medium, or high) and framing of discount (monetary or percentage) on perceived attractiveness of discount amount[J]. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 2019, 18(1): 76–85. |

| [58] | Li W, Hardesty D M, Craig A W, et al. Hidden price promotions: Could retailer price promotions backfire?[J]. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 2022, 64: 102797. |

| [59] | Lichtenstein D R, Netemeyer R G, Burton S. Distinguishing coupon proneness from value consciousness: An acquisition-transaction utility theory perspective[J]. Journal of Marketing, 1990, 54(3): 54–67. |

| [60] | Lim S, Ok C. A percentage-off discount versus free surcharge: The impact of promotion type on hotel consumers’ responses[J]. Tourism Management, 2022, 91: 104504. |

| [61] | Liu M W, Wei C, Yang L, et al. Feeling lucky: How framing the target product as a free gift enhances purchase intention[J]. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 2022, 39(2): 349–364. |

| [62] | Lu Z, Bolton L E, Ng S, et al. The price of power: How firm’s market power affects perceived fairness of price increases[J]. Journal of Retailing, 2020, 96(2): 220–234. |

| [63] | Lu Z Y, Hsee C K. Less willing to pay but more willing to buy: How the elicitation method impacts the valuation of a promotion[J]. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 2019, 32(3): 334–345. |

| [64] | Maguire R, Maguire P, Keane M T. Making sense of surprise: An investigation of the factors influencing surprise judgments[J]. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 2011, 37(1): 176–186. |

| [65] | Martins M, Monroe K B. Perceived price fairness: A new look at an old construct[C]. In Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 21, Allen C T, John D R, eds. Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, 75-78. |

| [66] | Mazar N, Shampanier K, Ariely D. When retailing and Las Vegas meet: Probabilistic free price promotions[J]. Management Science, 2017, 63(1): 250–266. |

| [67] | Mela C F, Gupta S, Lehmann D R. The long-term impact of promotion and advertising on consumer brand choice[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 1997, 34(2): 248–261. |

| [68] | Monroe K B. Buyers’ subjective perceptions of price[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 1973, 10(February): 70–80. |

| [69] | Moon A, Nelson L D. The uncertain value of uncertainty: When consumers are unwilling to pay for what they like[J]. Management Science, 2020, 66(10): 4686–4702. |

| [70] | Mori R J. It’s not price; It’s quality. Satisfaction and price fairness perception[J]. World Development, 2021, 139: 105302. |

| [71] | Mukherjee A, Jha S, Smith R J. Regular price $299; pre-order price $199: Price promotion for a pre-ordered product and the moderating role of temporal orientation[J]. Journal of Retailing, 2017, 93(2): 201–211. |

| [72] | Newman G E, Mochon D. Why are lotteries valued less? Multiple tests of a direct risk-aversion mechanism[J]. Judgment and Decision Making, 2012, 7(1): 19–24. |

| [73] | Oly Ndubisi N, Tung Moi C. Customers behaviourial responses to sales promotion: The role of fear of losing face[J]. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 2005, 17(1): 32–49. |

| [74] | Pai F Y, Chen C P, Yeh T M, et al. The effects of promotion activities on consumers’ purchase intention in chain convenience stores[J]. International Journal of Business Excellence, 2017, 12(4): 413. |

| [75] | Sailors J J, Heyman J E. Compound anchors and their subsequent effects on judgments[J]. American Behavioral Scientist, 2011, 55(8): 1035–1051. |

| [76] | Schmidt L, Bornschein R, Maier E, et al. The effect of privacy choice in cookie notices on consumers’ perceived fairness of frequent price changes[J]. Psychology & Marketing, 2020, 37(9): 1263–1277. |

| [77] | Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague P R. A neural substrate of prediction and reward[J]. Science, 1997, 275(5306): 1593–1599. |

| [78] | Simonson I, Drolet A. Anchoring effects on consumers’ willingness-to-pay and willingness-to-accept[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 2004, 31(3): 681–690. |

| [79] | Tan H Y, Akram U, Sui Y. An investigation of the promotion effects of uncertain level discount: Evidence from China[J]. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 2019, 31(4): 957–979. |

| [80] | Tan W K, Chen B H. Enhancing subscription-based ecommerce services through gambled price discounts[J]. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 2021, 61: 102525. |

| [81] | Tang J, Zhou J, Zheng C, et al. More expectations, more disappointments: Ego depletion in uncertain promotion[J]. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 2022, 66: 102916. |

| [82] | Thaler R. Mental accounting and consumer choice[J]. Marketing Science, 1985, 4(3): 199–214. |

| [83] | Thaler R. Transaction utility theory[A]. Bagozzi R P, Tybout A M. NA-advances in consumer research[M]. Ann Abor: Association for Consumer Research, 1983. |

| [84] | Tversky A, Kahneman D. Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty[J]. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 1992, 5(4): 297–323. |

| [85] | Tversky A, Shafir E. The disjunction effect in choice under uncertainty[J]. Psychological Science, 1992, 3: 305–309. |

| [86] | Urbany J E, Madden T J, Dickson P R. All’s not fair in pricing: An initial look at the dual entitlement principle[J]. Marketing Letters, 1989, 1(1): 17–25. |

| [87] | Valenzuela A, Mellers B, Strebel J. Pleasurable surprises: A cross-cultural study of consumer responses to unexpected incentives[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 2009, 36(5): 792–805. |

| [88] | Wang P, Du R, Hu Q. How to promote sales: Discount promotion or coupon promotion?[J]. Journal of Systems Science and Systems Engineering, 2020, 29(4): 381–399. |

| [89] | Wilson T D, Centerbar D B, Kermer D A, et al. The pleasures of uncertainty: Prolonging positive moods in ways people do not anticipate[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2005, 88(1): 5–21. |

| [90] | Wong K F E, Kwong J Y Y. Is 7300 m equal to 7.3 km? Same semantics but different anchoring effects[J]. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 2000, 82(2): 314–333. |

| [91] | Wu C S, Cheng F F, Lin H H. Exploring anchoring effect and the moderating role of repeated anchor in electronic commerce[J]. Behaviour & Information Technology, 2008, 27(1): 31–42. |

| [92] | Yang B, Mattila A S. How rational thinking style affects sales promotion effectiveness[J]. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 2020, 84: 102335. |

| [93] | Zhu P, Wang Z, Li X, et al. Understanding promotion framing effect on purchase intention of elderly mobile app consumers[J]. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 2020, 44: 101010. |