2022第44卷第9期

大多数人都会经历恋爱、结婚的人生阶段,浪漫伴侣和婚姻关系是成年人生活中非常重要的内容。一段浪漫关系涉及追求伴侣、维系伴侣甚至面临关系破裂等内容(Buss,2000;Morris等,2015)。从生物学的角度来说,能否获得一个异性伴侣决定了个体基因是否能够延续(Buss,2000,2006;Griskevicius和Kenrick,2013);从社会学的角度来说,浪漫关系也为个体提供了重要的情感依附和社会支持(Liu等,2020;Rokach和Brock,1998)。近年来,相关学者从进化心理学的视角探索了个体为了解决适应性问题而采取的配偶策略的内容,其进化适应的功能和对个体心理、认知和行为的影响(例如,Buss,1989;Griskevicius等,2007;Vandenbroele等,2020)。

配偶策略(mate tactic)是指个体在解决适应性问题动机的作用下采取的行为策略,例如,当浪漫关系或婚姻关系中存在第三者时,个体会采取嫉妒和配偶保卫等配偶维系策略(Buss,2002,2006,2007)。一旦某个配偶策略被激活,便会促发特定的行为,因为该行为体现了与该配偶策略相对应的进化适应功能(Buss,2002;Griskevicius等,2007)。在经济社会中,消费具有特定的社会意义,人们的行为或者人际互动往往诉诸于消费行为(Ding等,2020;Veblen,1994),因此配偶策略影响的个体行为可能直接体现在某些消费行为中,而这些消费行为恰好表征了特定的进化适应功能(Borau等,2021;Griskevicius等,2007;Wang和Griskevicius,2014)。例如,当个体的配偶吸引动机被激活时,男性会购买奢侈品,女性会实施慈善行为(Griskevicius等,2007),这是因为奢侈品消费具有展示物质财富的功能,慈善行为有表征慈爱品质的功能,而这样的特征品质(例如,男性的物质财富、女性的慈爱品质)是进化适应的优良配偶特质,有助于繁衍、孕育和抚养后代(Buss,1989;Buss和Schmitt,1993)。消费行为领域的国际期刊Journal of Consumer Psychology早在2013年就开设了对话专刊,讨论进化适应的根本动机对消费行为的影响,并提出了“进化适应的消费行为”(evolutionary consumption)概念(Griskevicius和Kenrick,2013;Saad,2013)。Buss和Foley(2020)也提出了配偶吸引等配偶策略对市场营销的重要影响,并且Psychology & Marketing和Journal of Business Research分别于2021年2月和 2020年11月刊发了关于进化适应和消费行为的专题(例如,Russell等,2021;Saad,2020)。目前,关于进化适应对消费行为影响的研究多聚焦于配偶策略的作用(例如,Buss和Foley,2020;Wang和Griskevicius,2014)。

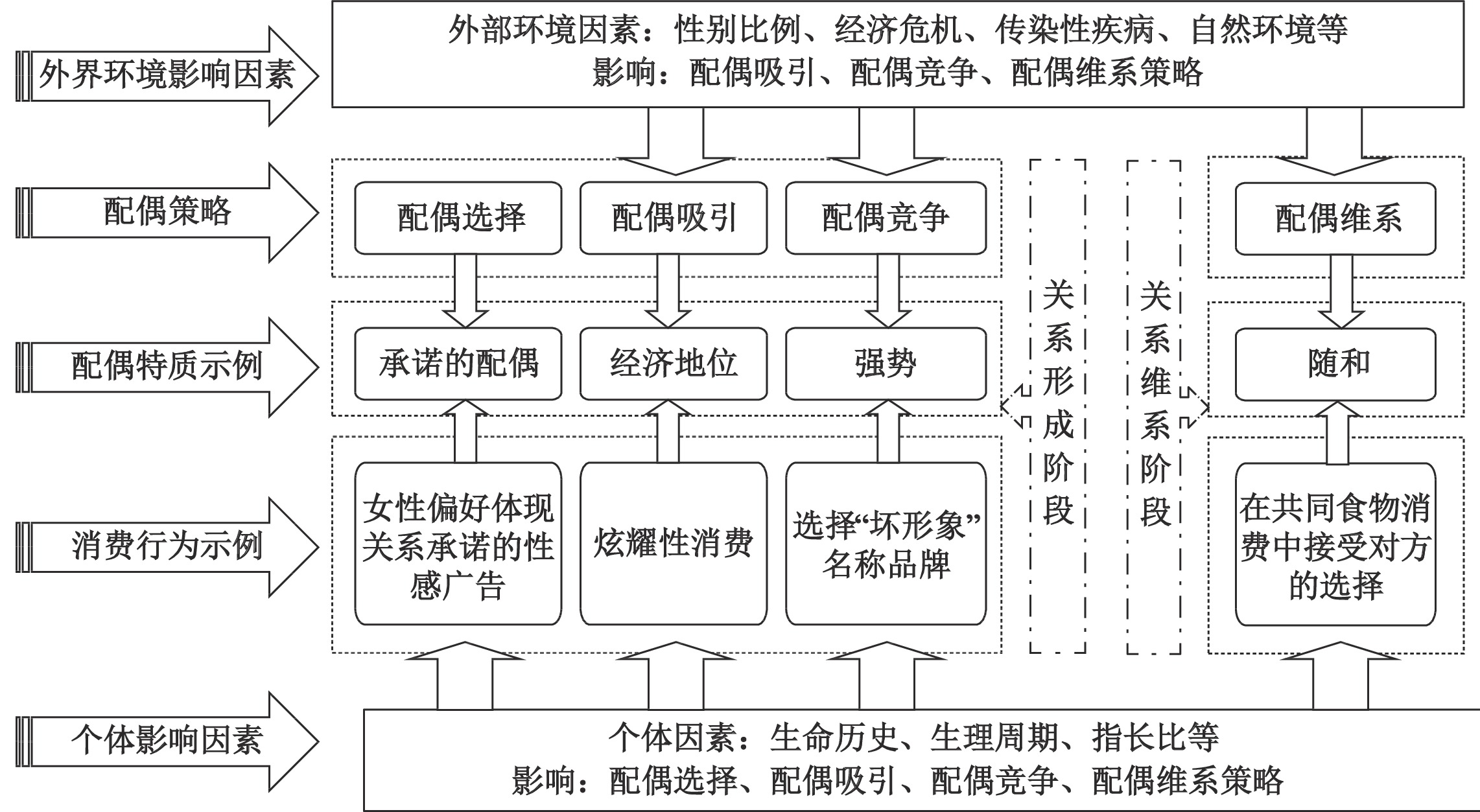

关于配偶策略对消费心理和行为影响的研究已经形成了一定的脉络,但是鲜有文章系统地梳理配偶策略之间的关系及配偶策略促发的消费行为。鉴于此,本文希望通过构建配偶策略系统,系统地、综合地梳理、归纳该领域的研究内容、脉络和范式,并结合配偶策略系统梳理相关消费表征。另外,本文还总结了影响个体配偶策略系统与相关消费行为的外界环境因素和个体因素。本文由以下几部分组成:首先,阐明了配偶策略系统的内容及其进化适应功能。配偶策略系统分为浪漫关系形成阶段和浪漫关系维系阶段,其中前者包含配偶选择策略、配偶吸引策略和配偶竞争策略,后者包含配偶维系策略。其次,总结了具体配偶策略对消费行为的直接影响。在配偶策略的驱动下,个体进行具有特定进化适应功能的消费行为。再者,梳理了外部环境因素和个体因素对配偶策略系统与消费行为的影响。由于外部环境和个体因素会促发或影响个体的配偶策略系统,因此相关研究探索了促发配偶策略系统的外部环境因素和个体因素如何进一步作用于消费行为。最后,提出了未来研究方向。未来的研究可以继续丰富配偶策略系统与相应的消费表征,深入探究影响配偶策略系统的外部环境因素和个体因素,并明确配偶策略系统如何泛化影响与配偶获取或维系无关的消费行为。总的来说,配偶策略系统促发的消费心理和行为是心理学领域和营销领域正在不断发展的一个研究热点,而国内的相关研究还较为少见。国内学者袁少锋(2014)以及张雷和朱小琴(2014)总结了各类进化需求作为一种根本动机对消费决策的影响,其中就包括繁衍动机下消费者的消费决策与行为,例如个体为了吸引配偶而进行的炫耀性消费行为,但是这两篇文献并没有系统地综述配偶策略系统中具体配偶策略对消费行为的影响。因此,本文的意义在于:首先,创新性地构建了配偶策略系统,梳理了配偶策略与相关的消费行为;其次,总结了影响配偶策略系统的外部环境因素和个体因素,有利于更全面地理解配偶策略与进化适应行为;最后,提炼了配偶策略系统的研究薄弱点和未来研究方向。本文期望通过对该领域成果的梳理和综述,促进国内该领域研究的发展。

二、配偶策略系统Buss(1988a)根据达尔文的自然选择理论提出,求偶行为是被自然选择逻辑结构化的行为。结合Buss(1988a,2000)、Janssens等(2011)等研究,本文认为成功的求偶行为是个体首先通过选择过程将组成配偶池的潜在配偶缩减到一个或几个,并通过配偶吸引、配偶竞争等方式获取配偶,然后再使用相关策略维系已经获得的配偶。因此,成功的求偶行为包括两个阶段(Buss,2000;Hasford等,2018;Wang和Griskevicius,2014),首先是关系形成阶段(formation stage),个体选择符合自己偏好特征的配偶并采取一定的策略获取配偶(mate acquisition),具体有配偶选择(mate selection)(Buss,1989)、配偶吸引(mate attraction)(Griskevicius等,2007)、配偶竞争(mate competition)(Buss,1988b)等策略;其次是关系维系阶段(maintenance stage),个体通过配偶维系(mate retention)等基本策略(Buss,2006;Wang和Griskevicius,2014)维系与配偶的关系。这些获取与维系配偶相关策略共同组成配偶策略系统,促使个体进行特定的行为,这些行为是相关策略的直接功能表达,表征了与相应配偶策略相对应的进化适应功能(Buss,2002;Griskevicius等,2007)。

从生物学的角度来说,大多数的男性和女性都需要异性配偶来繁衍后代,个体首先需要在配偶池中选择合适的配偶。配偶选择是指寻找具有自己期望的优良配偶特质的异性,例如男性更看重配偶的年轻美貌,这样的特质对于后代的繁衍抚育有重要的作用;而女性更看重配偶良好的经济前景和较高的社会地位,这样的特质可以保障自己和后代的生存资源(Buss,1989,2000;Sundie等,2020)。另外,女性在选择配偶时更挑剔(Sundie等,2011),而男性在浪漫关系中是被挑选的一方(Chen等,2021);女性更可能追求长期配偶关系(long term mating strategy),而男性更可能追求短期配偶关系(short term mating strategy)(Jackson和Kirkpatrick,2007)。其次,在明确了理想的配偶对象后,个体需要展示自己积极的配偶特质来吸引配偶,例如人们在社交平台炫耀自己的跑步路线来展示自己健康的身体和优良的基因(Vandenbroele等,2020),人们也会在征婚广告中对这些积极的配偶特质进行展示(Greenlees和McGrew,1994;Koestner和Wheeler,1988)。此外,在个体获取配偶的过程中往往存在其他竞争者,当存在多个同性竞争者时,配偶竞争策略促使个体展现外表吸引力等相关特质,使自己在竞争者中脱颖而出占据优势,从而获得配偶(Buss,1988b)。

对于人类来说,只获得配偶不意味着成功的繁殖,个体还需要维系与配偶的关系。配偶维系策略主要包括管理潜在浪漫竞争对手威胁的行为和维系当前浪漫关系的积极行为两个方面(Griskevicius和Kenrick,2013)。配偶保卫策略(mate guarding)是配偶维系策略中的重要策略,是由于存在第三者(mate poacher)以及配偶会受到诱惑而背叛自己引起的,配偶保卫是为了解决这两个适应性问题(Buss,2002)。个体为了保卫配偶,可以直接应对第三者威胁(例如,打架),也可以采取防御措施避免配偶的背叛(例如,让配偶戴戒指、不带配偶去有其他同性在场的聚会)(Buss,2002)。同时,嫉妒作为一种消极情绪体验,也在浪漫关系维系中发挥着重要作用,男性的嫉妒与性不忠的线索有关,而女性的嫉妒主要与情感不忠的线索有关(Buss,1988a,2007)。

特定的消费行为可以表征、强化相应的配偶特质,例如个体可以通过炫耀性消费来表现自己的经济地位从而达到吸引配偶的目的等(Griskevicius等,2007)。因此,本文接下来将分别梳理配偶策略系统的不同内容对消费行为的影响。相关总结如图1所示。

|

| 资料来源:本文作者整理。 图 1 配偶策略系统与消费表征 |

(一)关系形成阶段的配偶策略与消费行为

1.配偶选择策略

个体的配偶选择偏好会影响其消费决策与消费行为,女性更倾向于追求有承诺的长期配偶关系,而不是随意的配偶关系(Buss和Schmitt,1993),这会影响她们对产品的选择和对性感(sexual imagery)广告的态度。例如,女性更不愿意购买在社交媒体上公开炫耀肌肉的男性网红推荐的产品,因为女性认为刻意展示自己肌肉的男性是为了吸引短期伴侣,不可能对关系做出承诺,这会影响女性对其推荐的产品的态度(Su等,2021);女性希望性被视为珍稀的、高贵的而不是随意的,因此女性对性感广告持负面态度,除非性感广告可以被解读为男性对关系的承诺(Dahl等,2009)或者被用于推广昂贵的产品(Vohs等,2014)。男性在选择配偶时更倾向于选择短期配偶关系(Jackson和Kirkpatrick,2007),也更容易接受没有承诺的性行为。因此性感广告会降低男性对浪漫相关产品和服务的偏好,因为性感广告会激活男性对即时性行为的追求,而对浪漫关系的追求会阻碍男性对即时性行为的追求;但是接触到长期浪漫关系广告不会降低男性对性相关产品的偏好(Ma和Gal,2016)。

2.配偶吸引策略

配偶吸引动机促使消费者采取特定的消费行为以达到吸引配偶的目的,例如购买他人可见的、体现自身优良配偶特质的产品(Griskevicius等,2007)。个体作为性伴侣的基因质量或适合度,可以通过可观察的特质表现出来(Kirsner等,2003)。女性通常基于资源和地位来评估男性的配偶价值,因此男性更可能进行炫耀性消费(Griskevicius等,2007;Panchal和Gill,2020;Roney,2003;Sundie等,2011)来展示自己的赚钱能力和地位,进行绿色消费(Borau等,2021;Griskevicius等,2010;Palomo-Vélez等,2021)或赠送礼物(Saad和Gill,2003)来展示自己的慷慨,或进行不从众消费(Griskevicius等,2006)等来吸引配偶。女性的炫耀性消费与男性不同,男性更看重配偶的亲社会特质,因此在激发女性的配偶获取动机后女性会表现出更强的亲社会行为(Griskevicius等,2007)。类似地,女性也可能会在浪漫关系的形成阶段表现得更平易近人以吸引潜在配偶,例如接受对方的食物选择(Hasford等,2018)。吸引配偶的动机会促使女性进行增强吸引力的消费行为,例如进行炫耀性消费(袁少锋等,2013)、化妆(Mafra等,2020)、选择热量更低的健康食物(Otterbring,2018)等。另外,吸引配偶的动机也会导致男性和女性都更喜欢冒险,例如男性会进行冒险投资(Kruger,2008;Li等,2012),女性可能会为了提升自己的外表吸引力而吃有健康风险的减肥药(Hill和Durante,2011)。

3.配偶竞争策略

配偶竞争是达尔文提出的性选择理论中的重要一环,繁殖成本更高的性别在选择配偶时拥有选择权,因此低成本的一方需要进行同性竞争才能获得交配权(Darwin,1871)。个体实现配偶竞争策略的方法不只有配偶吸引(Buss,1988b),还包括诋毁和操控竞争对手,以及转移潜在配偶的注意力等(Fisher和Cox,2011)。虽然Janssens等(2011)提出成功的繁殖涉及配偶选择和配偶吸引两个子目标,但是配偶竞争策略是获取配偶的过程中重要且不可缺失的一环。例如,Buss(2000)提到,个体成功繁殖面临的适应性问题就包括配偶竞争;Senyuz和Hasford(2022)研究认为,在形成浪漫关系的过程中往往存在竞争对手,为了赢得竞争,个体可能需要贬低竞争者并推销自己,这种思维范式会导致具有浪漫关系形成动机的个体更喜欢傲慢的品牌。因此,配偶竞争策略是浪漫关系形成阶段的配偶策略之一。

获取配偶的过程中存在其他同性竞争者(Buss,1988b),个体可以通过特定的消费行为解决配偶竞争的适应性问题。例如,女性可以通过消费奢侈品提升自己的吸引力(Buss,1988b;Hudders等,2014;Zhao等,2017),但是具有配偶竞争意识的女性在购物过程中会更相信男同性恋销售助理(Russell等,2021)。配偶竞争也会使男性在外表打扮上下更大的功夫,包括穿戴好看的衣着首饰、改变发型、喷香水(Fisher和Cox,2011)、进行炫耀性消费(Hennighausen等,2016)等。除了打扮自己使外表更具吸引力,男性也会在同性竞争中展示物质资源(Buss,1988b)、购买“坏形象”名称品牌(negative brand)(“坏形象”名称是指带有破坏力量的负面效价的品牌名称,如“风暴”香水)以展现出强势来赢得同性竞争(King和Auschaitrakul,2021)。

(二)关系维系阶段的配偶策略与消费行为

在获得配偶之后,男女双方都会积极主动地采取策略巩固和维系双方的关系,例如,男性投入时间做家务、营造共同参加的休闲活动,女性避免表达负面情绪(Schoenfeld等,2012);男性会按照配偶的喜好行事,表现得更随和来维系与配偶的关系,比如在女性更擅长的食物领域,男性通常接受配偶的选择而忽略自己的需求(Hasford等,2018;Richerson等,2020)。Garcia-Rada等(2019)发现,无论是男性还是女性都可能会更多地考虑对方的情感反应和愉悦程度,选择自己不太喜欢的产品。

此外,在维系配偶关系的过程中,还可能会面临第三者插足与配偶背叛问题(Buss,2002),因此个体要通过配偶保卫策略来保卫配偶。当存在第三者时,个体可以直接面对第三者,也可以使用更微妙的策略,向其他同性表达自己的伴侣对自己深深的关心,并对关系做出承诺(Buss,1988a),这样第三者就不太可能追求自己的伴侣(Schmitt和Buss,2001)。炫耀性消费既可以吸引配偶,也可以维系与配偶的关系(Griskevicius等,2007)。Wang和Griskevicius(2014)发现,启动一名女性保卫配偶的动机会促使她进行炫耀性奢侈品消费,以此传达她与配偶“情比金坚”的信号,进而震慑对方。浪漫嫉妒是双方关系互动中很重要的情绪,可以帮助个体维系与配偶的浪漫关系(Buss,1988a)。DiBello等(2014)发现嫉妒会增加个体的饮酒行为。

从上述文献来看,现有研究关注了浪漫关系形成阶段和浪漫关系维系阶段个体的不同配偶策略与消费表征,但是研究主要集中于浪漫关系形成阶段,尤其是配偶吸引目标下个体的消费行为,而配偶维系目标下个体的消费行为研究尚显不足。

四、外部环境因素对配偶策略系统与消费行为的影响外部环境因素会促发或影响个体的配偶策略系统和消费行为。例如,Burtăverde和Ene(2021)发现,社会环境的安稳与否会影响女性的配偶选择偏好,在稳定的社会环境中,女性更看重男性的个人特质,而动荡的社会环境会使女性更看重男性获取资源的能力。社会因素,例如性别比例、经济危机,自然因素,例如自然环境、传染性疾病,都会影响个体获取配偶的过程和维系配偶的努力,进而影响消费行为。

(一)性别比例

性别比例主要通过影响配偶竞争强度来影响个体的行为(Kvarnemo和Ahnesjo,1996)。性别比例失衡导致个体求偶过程中存在更多的同性竞争,进而对人类的消费等行为产生诸多影响(邢采等,2012)。例如,性别比例失衡使得性别比例处于劣势(某性别个体的数量比异性多)的一方为了获得配偶,需要付出更多的求偶努力,他们不得不花费更多的资源来获取配偶,进而影响到财务决策或展示自身特质的消费行为(Griskevicius等,2012)。性别比例失衡也会对宏观经济产生影响(Wei和Zhang,2011)。

性别比例影响个体的配偶竞争策略,在女性较少的社会中,男性会加大求偶力度(Griskevicius等,2009),为求偶相关产品花费更多的钱,例如购买更贵的结婚戒指(Griskevicius等,2012)。性别比例还会影响人们的资产管理,比如在男性较多的环境中,男性更可能选择立刻能收到的短期收益而不是更多的长期收益、减少存钱的欲望、增加信用卡负债欲望(Griskevicius等,2012)。性别比例也会影响个体的配偶吸引策略,无论是男性还是女性,在性别比例处于不利地位时都更可能“将鸡蛋放入一个篮子里”,即在金融投资中进行集中投资。集中投资这种高风险策略暗示了一个人的野心和自信,可以帮助个体给潜在配偶留下好印象(Ackerman等,2016)。男性甚至会将酗酒作为自己时间、精力、资源等潜在品质的成本信号来吸引比较稀缺的异性,寻求短期浪漫关系。因为酗酒会对认知、精神和免疫系统造成负面影响,低价值的个体不具备产生和维系信号的能力,因此能够维系如此高成本的信号,就说明个体具有时间、精力、资源等高潜在品质,象征着个体的活力和高配偶价值(Aung等,2019)。对女性更多的性别比例失衡的研究比较少,Durante等(2012)发现性别比例失衡会影响女性的工作选择,在男性较少的环境中女性认为寻找高薪资工作比照顾家庭更重要。

性别比例失衡不只会影响个体的消费行为,也会在更宏观的层面上对宏观经济造成影响(李树茁和胡莹,2012;邢采等,2012)。在男性更多的环境中,配偶竞争导致有儿子的家庭推迟消费、增加储蓄(Du和Wei,2013;Wei和Zhang,2008)。另外,男性为了提高自己在婚恋市场上的相对地位,会追求更大、更昂贵的房子,进而导致房价的上涨(Wei等,2012;逯进和刘璐,2020)。性别比例还会影响地区GDP,由于家庭财富是婚姻市场中一个重要的地位变量,因此性别比例失衡使得人们(尤其是有儿子的家庭)积极创业、努力工作来创造财富为结婚做准备,从而创造更多的GDP(Wei和Zhang,2011)。Angrist(2002)通过调查移民数据发现,当社会环境中男性更多时,男性的收入增加,女性的劳动率降低;并且性别比例对劳动力供应决策的影响,在性别比例恢复到自然水平之后仍长期存在(Grosjean和Khattar,2019)。

(二)经济危机

经济因素对个体配偶策略系统的影响主要集中在关系形成阶段,例如经济危机影响配偶吸引策略和配偶竞争策略,进而导致相应的经济和消费行为。首先经济衰退会影响男性和女性的配偶吸引策略。经济萧条导致物资稀缺,使得女性更看重与获取资源有关的配偶特质(Lee和Zietsch,2011),例如经济衰退会使女性认为拥有奢侈品的男性更有吸引力,因此男性在短期配偶吸引动机的驱使下会增加对奢侈品的渴望(Bradshaw等,2020)。同时,经济衰退也会使女性投入更多精力来吸引具有优良物质基础的男性(Ellis等,2009),例如购买能增强自身吸引力的产品——口红(Hill等,2012)。

其次,经济衰退会影响男性的配偶竞争策略。White等(2013)发现,经济衰退导致低配偶价值的男性采取合作竞争的策略,例如有更多的亲社会行为、更支持政府的再分配政策;而高配偶价值的男性采取个人主义策略,因为他们在配偶竞争中有优势,渴望维系或增强现有优势,因此有更少的亲社会行为,更不支持政府的再分配政策。

(三)自然环境

影响人们的配偶策略系统的外部环境因素还包括自然环境,如光周期(日光长度的周期性变化)和飓风分别影响个体的配偶吸引和配偶维系策略。当处于日光长度长的季节时,人们的生育率更高,当广告涉及太阳时,人们会想到更长的光周期,男性因此会产生更强的性动机和积极情绪,这会增加男性对能够吸引配偶的奢侈品的偏好(El Hazzouri等,2020)。女性的求偶动机并不会受到太阳提示的影响,这是因为女性随生理周期波动的繁衍动机会产生更显著的影响(El Hazzouri等,2020;Griskevicius等,2007;陈瑞和郑毓煌,2015)。不只是光周期会影响人类的配偶策略系统,其他自然环境因素,例如飓风,也会影响人们的配偶策略系统。Williamson等(2021)发现,飓风会影响关系维系阶段新婚夫妇的婚姻满意度,具体来说,飓风会增加一段时间之内新婚夫妇的婚姻满意度,但是长期来看,满意度会恢复到飓风之前的水平。

(四)传染性疾病

疾病是人类在进化过程中经常遇到的影响生存的重大问题,因此人类对疾病也形成了一定的适应能力,传染性疾病对配偶策略系统的影响主要体现在配偶获取策略和配偶维系策略上。人们在新冠病毒流行期间具有疾病回避动机,因此倾向于与别人保持距离,但是对寻求新的浪漫伴侣更感兴趣的人,不会那么在意社交距离(Gul等,2021)。新冠疫情影响了人们获取配偶的方式,疫情期间的社交限制使人们更加孤独和无聊,与疫情之前相比,人们更多地通过在线约会软件寻找配偶,这会带来如沟通不畅、缺少承诺等消极影响(Chisom,2021)。另外,在新冠疫情的影响下,人们认为与关照家庭相关的动机(维系配偶、照顾亲人)比获取配偶的动机更重要,虽然在没有疫情影响时人们也认为与关照家庭相关的动机更重要(Ko等,2020;Pick等,2021),但是这更加说明配偶与家庭在养育后代、抵御外界威胁中起着重要作用。

通过上述文献总结可知,影响个体配偶策略系统与消费行为的外部环境因素,主要包括性别比例、经济危机、自然环境和传染性疾病四个方面,其中性别比例和经济危机属于社会因素,自然环境和传染性疾病属于环境因素。其中,有关社会因素中性别比例的研究较多,但是有关环境因素的研究较少,这可能是因为性别比例直接通过配偶竞争对配偶策略系统与消费行为造成影响,而环境因素如自然环境的影响更为复杂且不容易观察。

五、个体因素对配偶策略系统与消费行为的影响除了外部环境因素,个体因素也会促发或关联配偶策略系统,进而影响相关的消费行为。生命历史理论(life history theory)认为在获取配偶、养育后代等资源投入方面存在由童年时期生长环境的不同导致的成年之后的个体思维差异,并受到外界环境的影响(Griskevicius等,2011;Griskevicius等,2013;林镇超和王燕,2015)。另外,指长比和女性生理周期也会对配偶策略系统造成影响(Park等,2008;Saad和Stenstrom,2012;陈瑞和郑毓煌,2015)。

(一)生命历史

生命历史理论是关于个体在躯体努力(躯体的维系和成长)与繁衍努力(求偶和养育后代)中的资源分配策略的理论,不同的个体在资源分配上存在差异,因为资源分配会受到个体的成长经历和外界环境的影响(Hill等,2012;林镇超和王燕,2015)。个体早期的成长经历会影响其资源分配策略,恶劣的家庭成长环境会导致个体形成“快策略”(例如,更早性成熟,更多性伴侣,后代数量多),而在良好的家庭环境中成长的个体更可能形成“慢策略”(例如,更晚性成熟,更少性伴侣,注重后代教育)(林镇超和王燕,2015)。因此,从配偶策略系统的角度而言,“快策略”的个体比“慢策略”的个体在配偶获取上分配更多的资源。

在稳定的外界环境下,个体的资源分配等行为没有显著差异,但是在资源稀缺等外界环境的影响下,个体因成长经历所形成的“快策略”或“慢策略”会导致资源分配差异(Griskevicius等,2011,2013)。具体来说,在经济衰退时,在高社会经济地位环境中长大的个体更可能增加储蓄为未来规划,更不会冲动和冒险;而在社会经济地位较低的环境中长大的个体,更可能将钱花在提高现在的生活质量上,也会更冲动、更冒险(Griskevicius等,2013)。

(二)指长比

个体的指长比(digit ratio)是指在产前睾酮的影响下手指指长的比例关系,其中研究得比较多的是食指与无名指的比例关系(2D:4D),比值低意味着高产前睾酮,是更男性化的特征,比值高意味着低产前睾酮,是更女性化的特征(Nepomuceno等,2016;Van den Bergh和Dewitte,2006),它会影响消费者的配偶吸引策略、配偶竞争策略和配偶维系策略,进而影响消费行为。在配偶吸引策略方面,低指长比的男性更可能在娱乐、社交等领域冒险(Stenstrom等,2011)、购买彰显财富的产品(Nepomuceno等,2016)来吸引配偶,高指长比的女性更可能购买提升吸引力的产品以获取配偶(Nepomuceno等,2016)。在配偶竞争中,高指长比的男性更嫉妒高社会地位的竞争对手,低指长比的女性更嫉妒更有身体吸引力的竞争对手(Park等,2008)。个体指长比还会影响个体的配偶维系策略,低指长比的男性和高指长比的女性更可能赠送浪漫礼物维系与配偶的关系(Nepomuceno等,2016)。

(三)女性生理周期

女性的生理周期周期性地影响其配偶选择策略,使女性更偏好男性优良的基因,也会影响女性的配偶吸引策略,使她们更注重打扮自己以吸引潜在的配偶,同时还会影响女性的配偶竞争策略。女性在排卵期(vs.黄体期)具有强烈的繁育动机,在配偶选择中更注重能够体现基因质量的男性化面孔、低嗓音、创造力等特质(Haselton和Miller,2006;Penton-Voak和Perrett,2000;Puts,2005)和男性的社会地位(Lens等,2012)。女性在排卵期也具有追求、吸引配偶和性伴侣的动机,因此更可能进行自我装饰以吸引配偶(Saad和Stenstrom,2012),也更喜欢穿红色或粉色的衣服(Beall和Tracy,2013)。生理周期也会影响女性的配偶竞争策略。Durante等(2014)提出排卵竞争假说,也就是排卵期的女性需要与其他女性竞争才能成功地吸引到高基因质量的配偶,因此接近排卵期的女性会寻求地位商品来提高她们的社会地位,以吸引配偶;同时她们也会穿更性感的衣服来赢得同性竞争(Durante等,2011)。关于这一领域的研究,国内学者陈瑞和郑毓煌(2015)以及庄锦英和王佳玺(2015)已形成了较为系统的综述,本文不再详细展开。

综合上述文献可知,影响个体配偶策略系统与消费行为的个体因素包括生命历史、指长比和女性生理周期,尤其是女性生理周期,学者们进行了丰富的研究。生命历史理论对个体配偶策略与消费行为的研究主要是从个体童年经历的视角,而指长比和女性生理周期的影响则主要是从个体激素水平的视角。

六、总结与展望综上所述,进化适应的消费行为是近年来被提出的一个理论,多个国际期刊开设了对话栏目、专刊等探讨这一研究领域,该领域的研究更多地聚焦于配偶策略系统对消费行为的影响(例如,Buss和Foley,2020;Wang和Griskevicius,2014)。本研究构建了配偶策略系统,并结合配偶策略系统梳理了相应的消费表征,还探讨了影响配偶策略系统与消费行为的外部环境因素和个体因素。在外界环境的作用下,人们一天之内会多次想到与获取或者是维系配偶相关的事(Monga和Gürhan-Canli,2012),相关研究结果不仅为企业发现并利用消费者获取或维系配偶的动机提供了理论指导,也为学术界扩展和深化配偶策略系统及其消费表征奠定了研究基础。通过梳理配偶策略系统对消费行为影响的研究,本文总结提出以下未来研究方向:

第一,未来的研究可以更多地探索配偶维系阶段的策略和相应的消费行为。以往配偶策略系统对个体消费行为影响的研究主要集中在配偶关系形成阶段,有关配偶关系维系阶段消费行为的研究较少(Richerson等,2020;Wang和Griskevicius,2014)。但是,相比配偶关系建立,配偶关系维系对社会和谐和个体幸福更为重要,个体也更加看重配偶关系维系(Ko等,2020)。配偶关系的维系涉及个体化解关系危机和主动增进双方关系的行为(Ogolsky等,2017)。未来的研究可以探讨具体的配偶关系维系策略(例如,贬低潜在威胁者、双方互动)以及这些策略作用下的消费行为和这样的消费行为的功能价值。同时,在浪漫关系维系过程中可能出现配偶不忠(infidelity)的情况(Fisher等,2009;Tagler和Jeffers,2013),对配偶的不忠可能导致的愧疚等情感会如何影响个体的消费行为,也是一个有待探究的方向。

第二,除了配偶关系建立和配偶关系维系,人们还存在其他一些配偶策略,如配偶关系破裂(relationship breakup)和配偶关系转换(mate switching),这在现代社会非常普遍,例如《2020年民政事业发展统计公报》显示,2020年我国离婚人口数量为373.6万对,离婚率为3.1‰(中华人民共和国民政部,2021)。配偶关系破裂是指基于一方或双方的选择导致的浪漫关系或婚姻关系的结束(Morris等,2015),它会对个体的心理和生理造成极大的损伤(Field,2011),导致个体减少情感表达,进行情感回避和独立自主行为(Davis等,2003)。为了缓解关系破裂造成的伤害,男性和女性有不同的应对策略,女性更可能向同性好友倾诉,而男性会很快开始下一段约会(Priest等,2009)。未来的研究可以继续探究个体关系破裂后的其他具体适应性行为,以及这些行为对消费行为的影响。配偶关系转换是指配偶离开一段浪漫关系进入另一段浪漫关系,这在许多文化中都很常见。配偶转换假说认为,人类进化过程中对配偶转换的适应性问题形成了适应能力,以预测和评估配偶转换的机会,实施退出策略,并应对随之而来的挑战(Buss等,2017)。配偶转换中不仅存在对新浪漫配偶的吸引,还涉及评估新浪漫配偶的价值和浪漫兴趣、减少对前任配偶造成的伤害或者减少前任配偶对自己造成的伤害(Buss等,2017),或许还存在对原来配偶的愧疚,未来的研究可以深入探讨这些适应性行为对消费决策的影响。

第三,未来的研究可以进行更广泛和深入的外部环境因素和个体因素探索。光周期等自然环境因素会促发个体的配偶策略系统,但是除了光周期,在漫长的进化过程中,影响人类生存条件、对人类造成影响的自然环境因素还有很多,其他自然环境因素是否会以及会如何影响个体的配偶策略系统呢?除了自然环境因素,文化等社会环境因素也可能影响个体的配偶策略。Shanks等(2015)研究发现,配偶获取动机并不显著影响被试的冒险行为、损失厌恶行为,以及炫耀性消费行为。这引发了人们对进化心理学影响人类行为程度的思考,对于人类祖先曾经面临的问题,人类在进化过程中形成了一定的适应能力,但是这种适应能力可能在不同时代的文化价值观下展现程度有所不同或者受个体因素干扰较大。例如,新时代女性价值观发生了改变,不再像她们的祖先一样看重婚姻,越来越多的女性采取短期配偶策略(Buss和Schmitt,1993),在对婚姻不满意的时候也更可能主动提出离婚(Parker等,2022),这在一定程度上与进化心理学的相关研究结论背道而驰。但与此同时,新时代女性仍然受到传统性别刻板印象枷锁的限制,打拼事业的大龄单身女性认为她们总有一天会成为妻子和母亲,未来她们可能不得不在家庭和事业之间做出取舍,或成为“超级女人”(Gui,2020)。新时代价值观对传统价值观的冲击会影响男性和女性获取配偶和维系配偶的策略,未来的研究可以继续深入探讨配偶策略系统影响相关消费行为的文化价值观和个体因素等边界条件,来进一步验证进化心理学对人类行为影响的有效性。

第四,配偶策略系统还会对与求偶无关的心理和行为决策产生影响。例如,接触到浪漫刺激后,人们会更喜欢偶数(Kim,2020)、更喜欢甜食(Yang等,2019),对配偶承诺的思维会影响个体对产品的承诺(Chen等,2016)等,配偶选择等领域形成的思维会泛化影响其他领域的信息处理和决策。这说明配偶相关动机作为根本性动机在更广泛的意义上影响或改变了人们的思维,而不是仅限于配偶相关领域,本文受篇幅所限并未展开综述。未来的研究可以继续探讨配偶策略系统的思维泛化对其他非求偶消费行为的影响。

| [1] | 陈瑞, 郑毓煌. 进化的女性生理周期: 波动的繁衍动机和行为表现[J]. 心理科学进展, 2015, 23(5): 836–848. |

| [2] | 李树茁, 胡莹. 性别失衡的宏观经济后果——评述与展望[J]. 人口与经济, 2012, 33(2): 1–9. |

| [3] | 林镇超, 王燕. 生命史理论: 进化视角下的生命发展观[J]. 心理科学进展, 2015, 23(4): 721–728. |

| [4] | 逯进, 刘璐. 性别失衡对房价的影响——来自中国城市的证据[J]. 人口学刊, 2020, 42(2): 5–16. |

| [5] | 邢采, 张希, 牛建林. 人口性别比例失衡对人类行为的影响[J]. 心理科学进展, 2012, 20(10): 1679–1689. |

| [6] | 袁少锋. 进化需求对消费者购买决策的影响研究述评与展望[J]. 外国经济与管理, 2014, 36(1): 46–54. |

| [7] | 袁少锋, 郑毓煌, 李宝库. 我能买来爱吗——配偶吸引目标对女性炫耀性消费倾向的影响[J]. 营销科学学报, 2013, 9(2): 39–55. |

| [8] | 张雷, 朱小琴. 根本动机的进化起源及与消费行为的关系[J]. 苏州大学学报(教育科学版), 2014, 2(4): 1–13. |

| [9] | 中华人民共和国民政部. 2020年民政事业发展统计公报[EB/OL]. http://www.mca.gov.cn/ article/sj/tjgb/ 202109/ 20210900036577.shtml, 2021-09-10. |

| [10] | 庄锦英, 王佳玺. 女性生理周期与修饰行为的关系[J]. 心理科学进展, 2015, 23(5): 729–736. |

| [11] | Ackerman J M, Maner J K, Carpenter S M. Going all in: Unfavorable sex ratios attenuate choice diversification[J]. Psychological Science, 2016, 27(6): 799–809. |

| [12] | Angrist J. How do sex ratios affect marriage and labor markets? Evidence from America’s second generation[J]. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2002, 117(3): 997–1038. |

| [13] | Aung T, Hughes S M, Hone L S E, et al. Operational sex ratio predicts binge drinking across U. S. counties[J]. Evolutionary Psychology, 2019, 17(3), doi: 10.1177/1474704919874680. |

| [14] | Barrett H C, Kurzban R. Modularity in cognition: Framing the debate[J]. Psychological Review, 2006, 113(3): 628-647. |

| [15] | Beall A T, Tracy J L. Women are more likely to wear red or pink at peak fertility[J]. Psychological Science, 2013, 24(9): 1837–1841. |

| [16] | Borau S, Elgaaied-Gambier L, Barbarossa C. The green mate appeal: Men’s pro-environmental consumption is an honest signal of commitment to their partner[J]. Psychology & Marketing, 2021, 38(2): 266–285. |

| [17] | Bradshaw H K, Rodeheffer C D, Hill S E. Scarcity, sex, and spending: Recession cues increase women’s desire for men owning luxury products and men’s desire to buy them[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2020, 120: 561–568. |

| [18] | Burtăverde V, Ene C. The influence of environmental and social characteristics on women’s mate preferences[J]. Personality and Individual Differences, 2021, 175: 110736. |

| [19] | Buss D M. From vigilance to violence: Tactics of mate retention in American undergraduates[J]. Ethology and Sociobiology, 1988a, 9(5): 291–317. |

| [20] | Buss D M. The evolution of human intrasexual competition: Tactics of mate attraction[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1988b, 54(4): 616–628. |

| [21] | Buss D M. Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures[J]. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1989, 12(1): 1–14. |

| [22] | Buss D M. Desires in human mating[J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2000, 907(1): 39–49. |

| [23] | Buss D M. Human mate guarding[J]. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 2002, 23(S4): 23–29. |

| [24] | Buss D M. Strategies of human mating[J]. Psihologijske Teme, 2006, 15(2): 239–260. |

| [25] | Buss D M. The evolution of human mating[J]. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 2007, 39(3): 502–512. |

| [26] | Buss D M, Foley P. Mating and marketing[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2020, 120: 492–497. |

| [27] | Buss D M, Goetz C, Duntley J D, et al. The mate switching hypothesis[J]. Personality and Individual Differences, 2017, 104: 143–149. |

| [28] | Buss D M, Schmitt D P. Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating[J]. Psychological Review, 1993, 100(2): 204–232. |

| [29] | Chen R, Shen H, Yang C M. Chooser or suitor? The effects of mating cues on men’s versus women’s reactions to commercial rejection[J]. Marketing Letters, 2021, doi: 10.1007/s11002-021-09594-4. |

| [30] | Chen R, Zheng Y H, Zhang Y. Fickle men, faithful women: Effects of mating cues on men’s and women’s variety-seeking behavior in consumption[J]. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2016, 26(2): 275-282. |

| [31] | Chisom O B. Effects of modern dating applications on healthy offline intimate relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the tinder dating application[J]. Advances in Journalism and Communication, 2021, 9(1): 12–38. |

| [32] | Dahl D W, Sengupta J, Vohs K D. Sex in advertising: Gender differences and the role of relationship commitment[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 2009, 36(2): 215–231. |

| [33] | Darwin C. The descent of man and selection in relation to sex[M]. London: John Murray, 1871. |

| [34] | Davis D, Shaver P R, Vernon M L. Physical, emotional, and behavioral reactions to breaking up: The roles of gender, age, emotional involvement, and attachment style[J]. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2003, 29(7): 871-884. |

| [35] | DiBello A M, Neighbors C, Rodriguez L M, et al. Coping with jealousy: The association between maladaptive aspects of jealousy and drinking problems is mediated by drinking to cope[J]. Addictive Behaviors, 2014, 39(1): 94–100. |

| [36] | Ding W, Pandelaere M, Slabbinck H, et al. Conspicuous gifting: When and why women (do not) appreciate men’s romantic luxury gifts[J]. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2020, 87: 103945. |

| [37] | Du Q Y, Wei S J. A theory of the competitive saving motive[J]. Journal of International Economics, 2013, 91(2): 275–289. |

| [38] | Durante K M, Griskevicius V, Cantú S M, et al. Money, status, and the ovulatory cycle[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 2014, 51(1): 27–39. |

| [39] | Durante K M, Griskevicius V, Hill S E, et al. Ovulation, female competition, and product choice: Hormonal influences on consumer behavior[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 2011, 37(6): 921–934. |

| [40] | Durante K M, Griskevicius V, Simpson J A, et al. Sex ratio and women’s career choice: Does a scarcity of men lead women to choose briefcase over baby?[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2012, 103(1): 121–134. |

| [41] | El Hazzouri M, Main K J, Shabgard D. Reminders of the sun affect men’s preferences for luxury products[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2020, 120: 551–560. |

| [42] | Ellis B J, Figueredo A J, Brumbach B H, et al. Fundamental dimensions of environmental risk[J]. Human Nature, 2009, 20(2): 204-268. |

| [43] | Field T. Romantic breakups, heartbreak and bereavement—Romantic breakups[J]. Psychology, 2011, 2(4): 382-387. |

| [44] | Fisher M, Cox A. Four strategies used during intrasexual competition for mates[J]. Personal Relationships, 2011, 18(1): 20–38. |

| [45] | Fisher M, Cox A, Tran U S, et al. Impact of relational proximity on distress from infidelity[J]. Evolutionary Psychology, 2009, 7(4): 560-580. |

| [46] | Garcia-Rada X, Anik L, Ariely D. Consuming together (versus separately) makes the heart grow fonder[J]. Marketing Letters, 2019, 30(1): 27–43. |

| [47] | Greenlees I A, McGrew W C. Sex and age differences in preferences and tactics of mate attraction: Analysis of published advertisements[J]. Ethology and Sociobiology, 1994, 15(2): 59–72. |

| [48] | Griskevicius V, Ackerman J M, Cantú S M, et al. When the economy falters, do people spend or save? Responses to resource scarcity depend on childhood environments[J]. Psychological Science, 2013, 24(2): 197–205. |

| [49] | Griskevicius V, Delton A W, Robertson T E, et al. Environmental contingency in life history strategies: The influence of mortality and socioeconomic status on reproductive timing[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2011, 100(2): 241–254. |

| [50] | Griskevicius V, Goldstein N J, Mortensen C R, et al. Going along versus going alone: When fundamental motives facilitate strategic (non)conformity[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2006, 91(2): 281–294. |

| [51] | Griskevicius V, Kenrick D T. Fundamental motives: How evolutionary needs influence consumer behavior[J]. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2013, 23(3): 372–386. |

| [52] | Griskevicius V, Tybur J M, Ackerman J M, et al. The financial consequences of too many men: Sex ratio effects on saving, borrowing, and spending[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2012, 102(1): 69–80. |

| [53] | Griskevicius V, Tybur J M, Gangestad S W, et al. Aggress to impress: Hostility as an evolved context-dependent strategy[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2009, 96(5): 980–994. |

| [54] | Griskevicius V, Tybur J M, Sundie J M, et al. Blatant benevolence and conspicuous consumption: When romantic motives elicit strategic costly signals[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2007, 93(1): 85–102. |

| [55] | Griskevicius V, Tybur J M, Van den Bergh B. Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2010, 98(3): 392–404. |

| [56] | Grosjean P, Khattar R. It’s raining men! Hallelujah? The long-run consequences of male-biased sex ratios[J]. The Review of Economic Studies, 2019, 86(2): 723–754. |

| [57] | Gui T H. “Leftover women” or single by choice: Gender role negotiation of single professional women in contemporary China[J]. Journal of Family Issues, 2020, 41(11): 1956–1978. |

| [58] | Gul P, Keesmekers N, Elmas P, et al. Disease avoidance motives trade-off against social motives, especially mate-seeking, to predict social distancing: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic[J]. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2021, doi: 10.1177/19485506211046462. |

| [59] | Haselton M G, Miller G F. Women’s fertility across the cycle increases the short-term attractiveness of creative intelligence[J]. Human Nature, 2006, 17(1): 50–73. |

| [60] | Hasford J, Kidwell B, Lopez-Kidwell V. Happy wife, happy life: Food choices in romantic relationships[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 2018, 44(6): 1238–1256. |

| [61] | Hennighausen C, Hudders L, Lange B P, et al. What if the rival drives a Porsche? Luxury car spending as a costly signal in male intrasexual competition[J]. Evolutionary Psychology, 2016, 14(4): 1–13. |

| [62] | Hill S E, Durante K M. Courtship, competition, and the pursuit of attractiveness: Mating goals facilitate health-related risk taking and strategic risk suppression in women[J]. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2011, 37(3): 383–394. |

| [63] | Hill S E, Rodeheffer C D, Griskevicius V, et al. Boosting beauty in an economic decline: Mating, spending, and the lipstick effect[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2012, 103(2): 275–291. |

| [64] | Hudders L, De Backer C, Fisher M, et al. The rival wears Prada: Luxury consumption as a female competition strategy[J]. Evolutionary Psychology, 2014, 12(3): 570–787. |

| [65] | Jackson J J, Kirkpatrick L A. The structure and measurement of human mating strategies: Toward a multidimensional model of sociosexuality[J]. Evolution and Human Behavior, 2007, 28(6): 382–391. |

| [66] | Janssens K, Pandelaere M, Van den Bergh B, et al. Can buy me love: Mate attraction goals lead to perceptual readiness for status products[J]. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2011, 47(1): 254–258. |

| [67] | Kim A. The effects of romantic motives on numerical preferences[J]. Psychology & Marketing, 2020, 37(9): 1231-1245. |

| [68] | King D, Auschaitrakul S. Affect-based nonconscious signaling: When do consumers prefer negative branding?[J]. Psychology & Marketing, 2021, 38(2): 338–358. |

| [69] | Kirsner B R, Figueredo A J, Jacobs W J. Self, friends, and lovers: Structural relations among Beck Depression Inventory scores and perceived mate values[J]. Journal of Affective Disorders, 2003, 75(2): 131–148. |

| [70] | Ko A, Pick C M, Kwon J Y, et al. Family matters: Rethinking the psychology of human social motivation[J]. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2020, 15(1): 173–201. |

| [71] | Koestner R, Wheeler L. Self-presentation in personal advertisements: The influence of implicit notions of attraction and role expectations[J]. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 1988, 5(2): 149–160. |

| [72] | Kruger D J. Male financial consumption is associated with higher mating intentions and mating success[J]. Evolutionary Psychology, 2008, 6(4): 603–612. |

| [73] | Kvarnemo C, Ahnesjo I. The dynamics of operational sex ratios and competition for mates[J]. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 1996, 11(10): 404–408. |

| [74] | Lee A J, Zietsch B P. Experimental evidence that women’s mate preferences are directly influenced by cues of pathogen prevalence and resource scarcity[J]. Biology Letters, 2011, 7(6): 892–895. |

| [75] | Lens I, Driesmans K, Pandelaere M, et al. Would male conspicuous consumption capture the female eye? Menstrual cycle effects on women’s attention to status products[J]. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2012, 48(1): 346–349. |

| [76] | Li Y J, Kenrick D T, Griskevicius V, et al. Economic decision biases and fundamental motivations: How mating and self-protection alter loss aversion[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2012, 102(3): 550–561. |

| [77] | Liu W, Guo Z Y, Chen R. Lonely heart? Warm it up with love: The effect of loneliness on singles’ and non-singles’ conspicuous consumption[J]. European Journal of Marketing, 2020, 54(7): 1523–1548. |

| [78] | Ma J J, Gal D. When sex and romance conflict: The effect of sexual imagery in advertising on preference for romantically linked products and services[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 2016, 53(4): 479–496. |

| [79] | Mafra A L, Varella M A C, Defelipe R P, et al. Makeup usage in women as a tactic to attract mates and compete with rivals[J]. Personality and Individual Differences, 2020, 163: 110042. |

| [80] | Monga A B, Gürhan-Canli Z. The influence of mating mind-sets on brand extension evaluation[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 2012, 49(4): 581–593. |

| [81] | Morris C E, Reiber C, Roman E. Quantitative sex differences in response to the dissolution of a romantic relationship[J]. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 2015, 9(4): 270–282. |

| [82] | Nepomuceno M V, Saad G, Stenstrom E, et al. Testosterone at your fingertips: Digit ratios (2D: 4D and rel 2) as predictors of courtship-related consumption intended to acquire and retain mates [J]. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2016, 26(2): 231–244. |

| [83] | Ogolsky B G, Monk J K, Rice T M, et al. Relationship maintenance: A review of research on romantic relationships[J]. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 2017, 9(3): 275-306. |

| [84] | Otterbring T. Healthy or wealthy? Attractive individuals induce sex-specific food preferences[J]. Food Quality and Preference, 2018, 70: 11–20. |

| [85] | Palomo-Vélez G, Tybur J M, van Vugt M. Is green the new sexy? Romantic of conspicuous conservation[J]. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 2021, 73: 101530. |

| [86] | Panchal S, Gill T. When size does matter: Dominance versus prestige based status signaling[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2020, 120: 539–550. |

| [87] | Park J H, Wieling M B, Buunk A P, et al. Sex-specific relationship between digit ratio (2D: 4D) and romantic jealousy[J]. Personality and Individual Differences, 2008, 44(4): 1039–1045. |

| [88] | Parker G, Durante K M, Hill S E, et al. Why women choose divorce: An evolutionary perspective[J]. Current Opinion in Psychology, 2022, 43: 300–306. |

| [89] | Penton-Voak I S, Perrett D I. Female preference for male faces changes cyclically: Further evidence[J]. Evolution and Human Behavior, 2000, 21(1): 39–48. |

| [90] | Pick C M, Ko A, Wormley A, et al. Family still matters: Human social motivation during a global pandemic[J]. PsyArXiv, 2021, doi: 10.31234/OSF.IO/Z7MJC. |

| [91] | Priest J, Burnett M, Thompson R, et al. Relationship dissolution and romance and mate selection myths[J]. Family Science Review, 2009, 14: 48-57. |

| [92] | Puts D A. Mating context and menstrual phase affect women’s preferences for male voice pitch[J]. Evolution and Human Behavior, 2005, 26(5): 388–397. |

| [93] | Richerson R, Mead J A, Li W J. Evolutionary motives and food behavior modeling in romantic relationships[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2020, 120: 509–519. |

| [94] | Rokach A, Brock H. Coping with loneliness[J]. The Journal of Psychology, 1998, 132(1): 107–127. |

| [95] | Roney J R. Effects of visual exposure to the opposite sex: Cognitive aspects of mate attraction in human males[J]. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2003, 29(3): 393–404. |

| [96] | Russell E M, Bradshaw H K, Rosenbaum M S, et al. Intrasexual female competition and female trust in gay male sales associates’ recommendations[J]. Psychology & Marketing, 2021, 38(2): 249–265. |

| [97] | Saad G. Evolutionary consumption[J]. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2013, 23(3): 351–371. |

| [98] | Saad G. The marketing of evolutionary psychology[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2020, 120: 485–491. |

| [99] | Saad G, Gill T. An evolutionary psychology perspective on gift giving among young adults[J]. Psychology & Marketing, 2003, 20(9): 765–784. |

| [100] | Saad G, Stenstrom E. Calories, beauty, and ovulation: The effects of the menstrual cycle on food and appearance-related consumption[J]. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2012, 22(1): 102–113. |

| [101] | Schmitt D P, Buss D M. Human mate poaching: Tactics and temptations for infiltrating existing mateships[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2001, 80(6): 894–917. |

| [102] | Schoenfeld E A, Bredow C A, Huston T L. Do men and women show love differently in marriage?[J]. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2012, 38(11): 1396–1409. |

| [103] | Senyuz A, Hasford J. The allure of arrogance: How relationship formation motives enhance consumer preferences for arrogant communications[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2022, 139: 106–120. |

| [104] | Shanks D R, Vadillo M A, Riedel B, et al. Romance, risk, and replication: Can consumer choices and risk-taking be primed by mating motives?[J]. Journal of Experimental Psychology:General, 2015, 144(6): e142–e158. |

| [105] | Stenstrom E, Saad G, Nepomuceno M V, et al. Testosterone and domain-specific risk: Digit ratios (2D: 4D and rel2) as predictors of recreational, financial, and social risk-taking behaviors [J]. Personality and Individual Differences, 2011, 51(4): 412–416. |

| [106] | Su Y R, Kunkel T, Ye N. When abs do not sell: The impact of male influencers conspicuously displaying a muscular body on female followers[J]. Psychology & Marketing, 2021, 38(2): 286–297. |

| [107] | Sundie J M, Kenrick D T, Griskevicius V, et al. Peacocks, Porsches, and Thorstein Veblen: Conspicuous consumption as a sexual signaling system[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2011, 100(4): 664–680. |

| [108] | Sundie J M, Pandelaere M, Lens I, et al. Setting the bar: The influence of women’s conspicuous display on men’s affiliative behavior[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2020, 120: 569–585. |

| [109] | Tagler M J, Jeffers H M. Sex differences in attitudes toward partner infidelity[J]. Evolutionary Psychology, 2013, 11(4): 821-832. |

| [110] | Van den Bergh B, Dewitte S. Digit ratio (2D: 4D) moderates the impact of sexual cues on men’s decisions in ultimatum games[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B:Biological Sciences, 2006, 273(1597): 2091–2095. |

| [111] | Vandenbroele J, Van Kerckhove A, Geuens M. If you work it, flaunt it: Conspicuous displays of exercise efforts increase mate value[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2020, 120: 586–598. |

| [112] | Veblen T. The theory of the leisure class[M]. New York: Dover, 1994. |

| [113] | Vohs K D, Sengupta J, Dahl D W. The price had better be right: Women’s reactions to sexual stimuli vary with market factors[J]. Psychological Science, 2014, 25(1): 278–283. |

| [114] | Wang Y J, Griskevicius V. Conspicuous consumption, relationships, and rivals: Women’s luxury products as signals to other women[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 2014, 40(5): 834–854. |

| [115] | Wei S J, Zhang X B, Liu Y. Status competition and housing prices[R]. NBER Working Paper No. w18000, 2012. |

| [116] | White A E, Kenrick D T, Neel R, et al. From the bedroom to the budget deficit: Mate competition changes men’s attitudes toward economic redistribution[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2013, 105(6): 924–940. |

| [117] | Williamson H C, Bradbury T N, Karney B R. Experiencing a natural disaster temporarily boosts relationship satisfaction in newlywed couples[J]. Psychological Science, 2021, 32(11): 1709–1719. |

| [118] | Yang X J, Mao H F, Jia L, et al. A sweet romance: Divergent effects of romantic stimuli on the consumption of sweets[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 2019, 45(6): 1213-1229. |

| [119] | Zhao T Y, Jin X T, Xu W, et al. Mating goals moderate power’s effect on conspicuous consumption among women[J]. Evolutionary Psychology, 2017, 15(3): 1–8. |